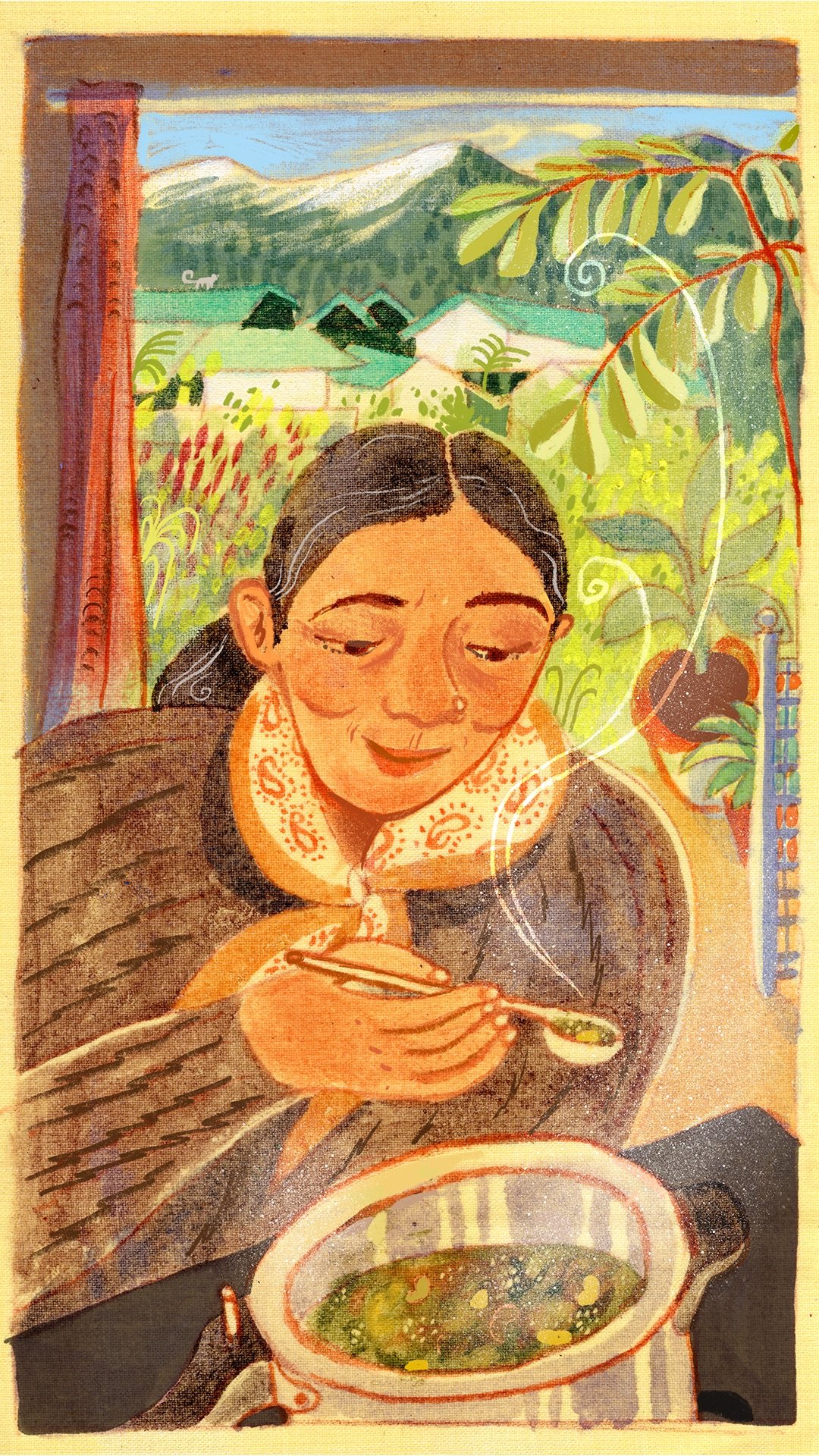

Indira Thakur makes a Himachali Winter Stew, Fembda

At Goya, celebrating home cooks and recipes have always been at the heart of our work. Through our series, #1000Kitchens, we document recipes from kitchens across the country, building a living library of heirloom recipes that have been in the family for 3 generations or more. In this edition, Krutika Behrawala learns about the hearty winter stew from Kullu, fembda, from Indira Thakur. Fembda is a flavour-rich, one-pot meal that falls under the staple of dishes born out of necessity and cold-weather wisdom of earlier generations

This season’s stories are produced in partnership with the Samagata Foundation—a non-profit that champions meaningful projects.

Bejewelled, a young bride in the 1960s, Indira Thakur travelled a short but momentous distance from the idyllic hamlet of Raison near Kullu to her new home in bustling Manali. She carried along a few prized possessions — a handwoven woollen pattu shawl carrying the familiar scent of home, embroidered Lahauli topis that had crowned her head during festivals, and her grandmother’s recipe of fembda — a hearty, winter stew that had fortified generations in her family against the biting cold of Himachal Pradesh.

Traditionally made in the Kullu region, fembda belongs to a repertoire of Himachali winter staples born out of necessity and ancestral cold-weather wisdom. Crafted for survival in a region with long spells of frost and scarcity, these dishes rely on heat-producing, nutrient-dense millets, pulses and grains like barley, buckwheat and amaranth, all grown on the Himalayan slopes.

In that sense, Indira says, fembda isn’t a “celebratory” or “festive” dish. Instead, it is a frugal but flavour-rich one-pot meal designed to keep families nourished when the winds coming in howling from the Pir Panjal ranges, as frost settles on rooftops, and fields sleep beneath the snow.

As a child, Indira watched her grandmother prepare fembda traditional way: a huge pot balanced on a clay chulha, its contents simmering as amber flames of woodfire lick the sides. “We had to wait patiently; it took almost an hour and a half to cook,” she says, remembering the warmth radiating from the hearth.

Today, the same dish cooks in a pressure cooker on the four-burner stove in her sleek and sun-kissed Manali kitchen. The space is immaculately organised, lined with mint green-laminated modular cabinets and modern appliances. An electric chimney hums softly above the stove. Indira’s kitchen mirrors Manali’s transformation over the past few decades—where home-cooked, seasonal mountain meals have given way to a rising tide of fast food-serving restaurants.

Yet despite this contemporary setting, Indira’s cooking remains firmly tethered to the lineage of women before her—deft, instinctive, and grounded in the seasonal produce of the land. So, local varieties of rajma, soyabean and red rice form the base of fembda, while its soul is salyara or amaranth. The latter may have found recent fame as a millennial “superfood” boasting of protein, fibre and naturally gluten-free virtues but the climate-resilient crop has long been a staple in the Himachali home.

“We have salyara specifically in winter because of its garam taseer,” Indira explains, referring to the natural warmth that it imparts. Amaranth takes the longest to soften while cooking fembda, but it’s what lends the stew its characteristic thickness and nutty depth, its “asli swaad”, as her grandmother liked to say. Each spoon of fembda pays homage to the rustic, laborious rhythms of Himachali farming life.

Indira, who comes from a long family of farmers, imbibed the joy of nurturing one’s own produce from her mother. “She would work tirelessly in the fields we owned and she would also tend to the cows and buffaloes we had. She never had time for anything else,” she says.

What the labour yielded was harvest—grains, vegetables, herbs and even ghee—that was pure, organic and free from preservatives. Amaranth, especially, grew in abundance. “Its grass is excellent feed for cows too. Everything was homegrown. In fact, it was considered shameful to buy anything from a store,” she laughs.

Today, Indira continues to stock her pantry with homegrown produce. She sources grains and pulses from her family’s fields; vegetables from her husband’s organic farms in Lahaul; herbs and spices from her backyard garden. She tempers fembda with some of them, coriander seeds, cumin, garlic and faran, a high-altitude variety of chives. She also folds in soaked saag or mountain greens that have been sun-dried and preserved for cold, winter months.

Indira ladles the steaming and fragrant fembda into bowls. “Today, the children don’t really enjoy it. They prefer pizza and burgers,” she says, glancing at her nine-year-old grandson reading at the dinner table. Though fembda is a complete meal, she has made potato momos too—her gentle way of coaxing him to try the traditional stew.

He does enjoy siddu, the fermented steamed wheat bread beloved in winter, along with thukpa and thenthuk. “So I add a fistful of amaranth to these dishes too,” chuckles the doting grandmother, on a mission to ensure that flavours and bounty of the hills endure, one bowl of fembda at a time.

RECIPE FOR FEMBDA

Serves up to 4 people

Ingredients

400 g rajma, soaked overnight

400 g soyabean

300 g salyara (amaranth)

400 g red rice

250 g dried greens

Salt, to taste

Red or green chilli, to taste (optional)

For tempering:

1 tbsp desi ghee (or 1 ladle measure)

7-8 garlic cloves, chopped

2 tbsp coriander seeds

2 tbsp cumin seeds

A fistful of dried chives

Method

Place soaked rajma, soyabean and amaranth in a pressure cooker with sufficient water. Cook for 2-3 whistles or until it softens.

Next, add red rice and boil until soft.

Soak dried greens in warm water for a few minutes. Add them to the stew along with salt and chilli (optional). Simmer for 15-20 minutes.

Heat ghee in a pan. Add garlic and sauté till the raw smell disappears.

Add the coriander seeds, cumin seeds and dried chives. Sauté lightly.

Pour the tempering over fembda. Mix well and serve hot.

Words by Krutika Behrawala. Photos by Terrence Manne. Artwork by Reshu.

Special thanks to our partners.

ALSO ON GOYA