Indian Delights: A Twice-Diasporic Cookbook with South African Roots

What does a cookbook that has been passed down generations in Mauritian Indian homes share in common with South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement? Ameerah Arjanee’s research into the seminal Indian Delights cookbook brings forth the story of how editor, Zuleikha Mayat, baked politics and Indian-African cultural hybridity into her book, inherently reimagining Indian Africans’ allyship with Afro-Mauritians in the 20th century.

During my childhood in Mauritius in the early 2000s, this book was the essential kitchen companion in every Indo-Mauritian Muslim household. It was edited by Zuleikha Mayat and published by the Women's Cultural Group in 1961. My nani owned two copies — one edition published in the 1970s, the other from the 1990s; both dog-eared from years of use and filled with handwritten notes in French and Creole. Every ‘respectable housewife’ in my community had a copy.

It took me some time to realise that Indian Delights wasn’t actually from India, but from South Africa. In a sense, the food that my grandmother and her friends learned to cook was twice-diasporic cuisine: made in Mauritius, with Mauritian ingredients, and based on a South African version of Indian cuisine, edited by Zuleikha Mayat, who was born in the 1920s as a first-generation South African with Gujarati parents.

The diasporic Indian communities of South Africa, Mauritius, Réunion Island and Kenya are connected through enduring networks of friendship, marriage and kinship. As a child, I’d hear matchmakers say “Li’nn gagn demann Lafrik Disid” (She’s received a marriage proposal from South Africa). Travellers, often daughters-in-law, brought copies of Indian Delights in their suitcase to gift to their families and friends back in Mauritius. Through their suitcases, women’s culinary knowledge travelled between the Indian diasporas of South Africa and Mauritius.

I asked women in my community to share their memories tied to the cookbook. Murshuda Joomye, a caterer in her 50s, says, “This book was gifted to me in 1991 from a South African friend. A few months later, I got married, and Indian Delights accompanied my first cooking experiences at my in-laws’ house. It is not just a book of recipes; it also tells stories about culture.”

A phone conversation with my friend, Shaheen Saliah Mohamed, about manze lakaz (home-cooked food) ended with her texting me a photo of Indian Delights that her mother had just lent her. I replied excitedly, “Oh, I have it too!”.

The author’s grandmother’s copy of Indian Delights.

Zuleikha Mayat was a first-generation South African with Gujarati parents.

I can still picture my grandma bustling around her kitchen around 2002. She was a passionate, energetic, and gloriously messy cook. There was always flour on her phone (she called her cousins to gossip while cooking!) and on her copy of Indian Delights, which was haphazardly thrown on the table next to a tepid mug of tea, open on the page she needed to consult. My grandmother passed away 13 years ago. Sometimes, when I ask mother, "To rapel nani so reset?" (Do you remember nani's recipe?), she just replies, "Bizin chek dan Indian Delights" (Look it up in Indian Delights). I still have her 1975 copy of the book, and I like to imagine that the whitish marks on its red cover aren’t just from age, but traces of where my nani’s flour-dusted hands once held it.

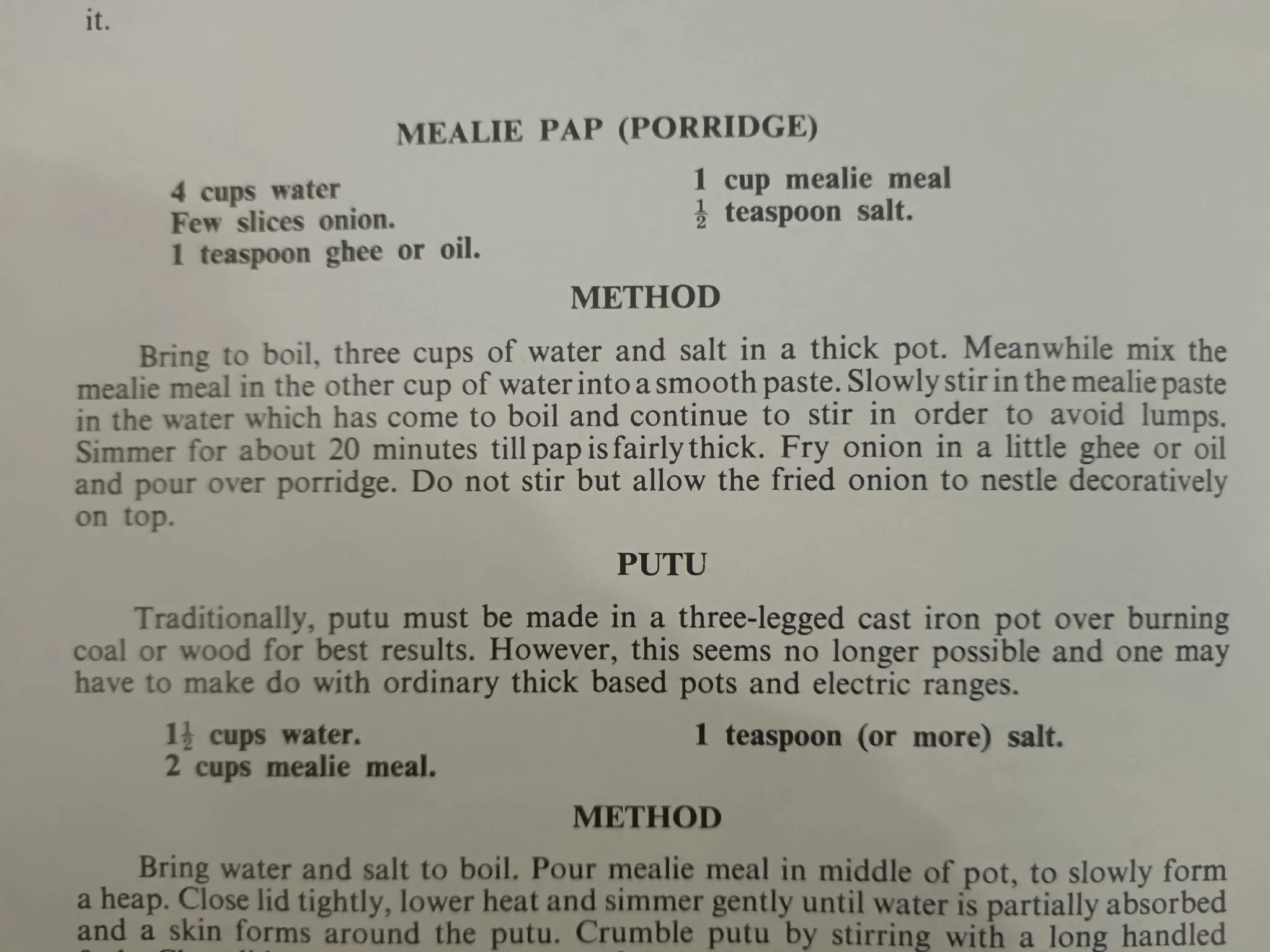

The book has distinctly diasporic recipes such as ‘Zanzibar murghi’, ‘Waikiki chicken’ and ‘mealie rotlas’ next to more recognisable Indian dishes like ‘moong dhal’ or ‘mutton kurma [korma]’. There is an entire section dedicated to recipes with mealie, a maize porridge that is a staple South African carb. In Zuleikha Mayat’s version of South African Indian cuisine, there exists a mealie rice biryani, a mealie bhajia, and a mealie rotla — the perfect blend of her dual Gujarati and South African identities.

Mealie pap is a maize porridge.

It is a staple South African carb.

Indian Delights has an entire section dedicated to dishes made with mealie pap (porridge).

Politics Baked into a Cookbook

Indian Delights is not only about the politics of care within the home. Zuleikha’s politics were also baked into her cookbook.

It was written in 1960s South Africa and is closely tied to anti-apartheid politics. Zuleikha Mayat was not only a home-maker and a cook, but also a committed anti-apartheid activist. She donated much of the money she earned from the sales of Indian Delights to the Women’s Cultural Group in Durban, which provided bursaries for the education of both Afro-Mauritian and Indian women. She also maintained close friendships with several prominent anti-apartheid figures, including Nelson Mandela and Ahmed Kathrada. As historian Saleem Badat notes, Mandela stayed at her and her husband’s home on multiple occasions while evading persecution by the authorities. During Kathrada’s time as a political prisoner on Robben Island, he and Mayat exchanged a series of letters that were later compiled by the historian Goolam Vahed. The book Gender, Modernity & Indian Delights: The Women’s Cultural Group of Durban, 1954–2010, co-written by Vahed and Thembisa Waetjen, details Zuleikha’s involvement in various anti-apartheid organisations such as the South African Institute of Race Relations and Black Sash.

She embraced Indian-African cultural hybridity. In her vision of Indian food in Durban, ingredients were not segregated. The photos in the cookbook also subtly advocated for an unsegregated society. One photo from my copy of the 1975 edition shows three women enjoying a picnic in the park: two of the friends are Indian, while the third is Afro-Mauritian — they are all smiling and fashionably dressed; no one is in a position of subservience.

The 1975 edition of the cookbook shows three women enjoying a picnic in the park — they are all smiling and fashionably dressed; no one is in a position of subservience.

The politics in both her cooking and wider life made me reflect on the patriarchal lens through which we define an activist. An activist isn’t necessarily a man on the streets; it can also be an elderly woman with a dupatta around her head who does the traditionally feminine job of cooking. Activism can be embedded in the networks of women sharing culinary knowledge. By buying and gifting so many copies of Indian Delights, weren’t the dadis and khalas of my Indo-Mauritian community, whether aware of it or not, funding the anti-apartheid struggle next door?

Zuleikha’s activism is also important because, historically, diasporic Indians in East Africa have occupied a fraught middle position between white colonisers and marginalised Africans. They have been small traders, policemen and administrative workers in post-plantation, apartheid and post-apartheid societies, and they have often had the choice to side with power. In modern-day Mauritius, this middle position is seen in the political arrangement that divides power between the white descendants of plantation owners and Indo-Mauritians. Economic power remains in the hands of white Mauritians; Indo-Mauritians dominate political parties; while Afro Mauritians are largely excluded from power. Even if most Indo-Mauritians have ancestors who were also exploited as indentured labourers on plantations, over the 19th and 20th centuries, they developed a political elite that now works hand-in-hand with white supremacy and participates in anti-Afro-Mauritian violence.

This is why Indian Delights and its presence in Indo-Mauritian homes feels so precious to me. It offers a different way of imagining Indian Africans’ allyship with Afro-Mauritians in the 20th century, an alternative history where we do not side with the oppressor. Beyond the patriarchal frameworks of state politics, quietly, in our dadis’ and khalas’ kitchens, in recipes of Zanzibar murghi and photos of Indian and Afro-Mauritian women eating together, a different political reality is shown to be possible. It simmers quietly into being, like kari (curry) on the stove.

Mealie pap and Mauritian rougay (stew).

Ameerah Arjanee is a Mauritian writer, translator, and lecturer. Her ancestors were indentured labourers from Bihar and traders from Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. She translates cookbooks and subtitles food shows.

Sources:

https://sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive_files/Dr-Zuleikha-Mayat-An-Appreciation-Saleem-Badat.pdf

https://theconversation.com/zuleikha-mayat-south-african-author-and-activist-who-led-a-life-of-courage-compassion-and-integrity-222765.

The book by Vahed and Waetjen.

ALSO ON GOYA

Neo-nomad cuisine of Central Asia | Terrence Manne