#1000Kitchens: Snigdha Sur's Phooler Bora is a Dish that Anchors her Family to Bengal

At Goya, celebrating home cooks and recipes have always been at the heart of our work. Through our series, #1000Kitchens, we document recipes from kitchens across the country, building a living library of heirloom recipes that have been in the family for 3 generations or more. In this edition, Snigdha Sur shares with Sneha Mehta a recipe for pumpkin fritters that has travelled with her family from pre-partition Bengal to her current home in New York. This season’s stories are produced in partnership with the Samagata Foundation—a non-profit that champions meaningful projects.

The first thing you notice is the sound.

A gentle hiss as a thin, pale batter meets hot oil. Then the fragrance unfurls, unmistakable and nostalgic: the grassy sweetness of pumpkin blossoms and the earthy warmth of rice flour toasting at the edges. It is the kind of smell that collapses distance. Between pre-partition Bengal and Chattisgarh, and between NYC boroughs, from Snigdha Sur’s compact East Village kitchen and her mother, Shakti’s, pumpkin patch in Rego Park, the Sur family is anchored to Bengal by phooler bora, or pumpkin flower fritters. The simple dish is a totem of the vast distances the family has traveled. And every summer, they get a short window to experience this seasonal delicacy, so much so that it's the one dish Snigdha invariably makes time to cook.

“If I see pumpkin flowers at a farmers’ market, I have to buy them,” she says. “It's instinctual. I’m drawn to them like a moth to a flame.”

Snigdha’s mother, Shakti, grew up in Madhya Pradesh (now Chhattisgarh), in a Bengali family that grew its own vegetables — pumpkin, squash, bottle gourd — all staples of Bengali home cooking far from Bengal. When she moved to the U.S. in 1987, her first homes were in the Bronx’s Parkchester and later Rego Park, both known for their Bengali immigrant enclaves. She found comfort and continuity through Jackson Heights, a hub for Indian groceries. “All Indian vegetables you get there,” she explained matter-of-factly. “Chingri, parval, everything.”

Even though Bengalis are known to be big fish eaters, they also have a deeply rooted vegetarian tradition that is seasonal and astonishingly inventive. In many ways, the region’s abundant produce — gourds, banana stem, raw jackfruit, pumpkin, eggplant, taro, and dozens of seasonal greens (known as shaak) —defines the cuisine. Nothing is wasted: peels (khosa bhaja) become fritters, stems (data) are stewed, and overripe vegetables turn into mash (bhorta). Even flowers (phool bhaja) — like the Surs’ beloved pumpkin blossoms — are dipped in batter and fried. A simple pumpkin plant can yield 10 different dishes when used from root to bloom — a zero-waste approach to cooking practiced long before it became a buzzword.

While this ingenuity is incredible to witness, its origins are rooted in struggle. Before the social reforms that took place in 1856, Indian widows were systemically marginalized in society (read more about Bengal’s widow cuisine). And with access to minimal resources, be it money or produce, they developed techniques to stretch every vegetable, plant, and grain to its maximum capacity. Bengal’s delta landscape faces frequent floods and cyclones, so people also regularly experienced crop failures and agricultural precarity. These environmental shocks, combined with colonial extraction and repeated famines, shaped Bengali food habits and left a lasting psychological and culinary imprint that continues today. And so, a highly resourceful culinary tradition, of never wasting and making do, was born.

The framework of Bengali meals reflects how the cuisine treats plants with the same attention to texture and complexity that other food cultures might reserve for meat. Each meal follows a multi-course structure, which is rooted in a sattvic vegetarian philosophy of creating balance and harmony from complex flavours.

“Bengalis don’t eat just one vegetable and dal. We need three vegetables, one non-veg, one dal, and one chutney at the end,” said Shakti. “We start with shukto — the bitter dish — because it’s scientifically good for digestion. Then bhaja — all kinds of fries. Then dal. Then vegetables. Then fish or chicken. Then a sweet chutney at the end — tomato, pineapple, mango, with sugar and spices.”

The phooler bora is eaten at the start of a meal, sometimes with moong dal and rice. Before it is cooked, a flowering pumpkin plant is a thing of beauty. Sheer yellow petals, bright as marigolds, traversed by pale green veins, burst outwards in exuberant radiance. When cut, they lose some of that vitality, drooping and limp when they’re lowered into the batter. They bruise easily and vanish quickly — you can’t store them in the fridge. Eating one feels like catching something alive and rare at its peak. How do you describe the taste of a flower? “It tastes like the flower,” Snigdha said simply. “I don’t know how to explain it — like how a rose tastes like a rose.”

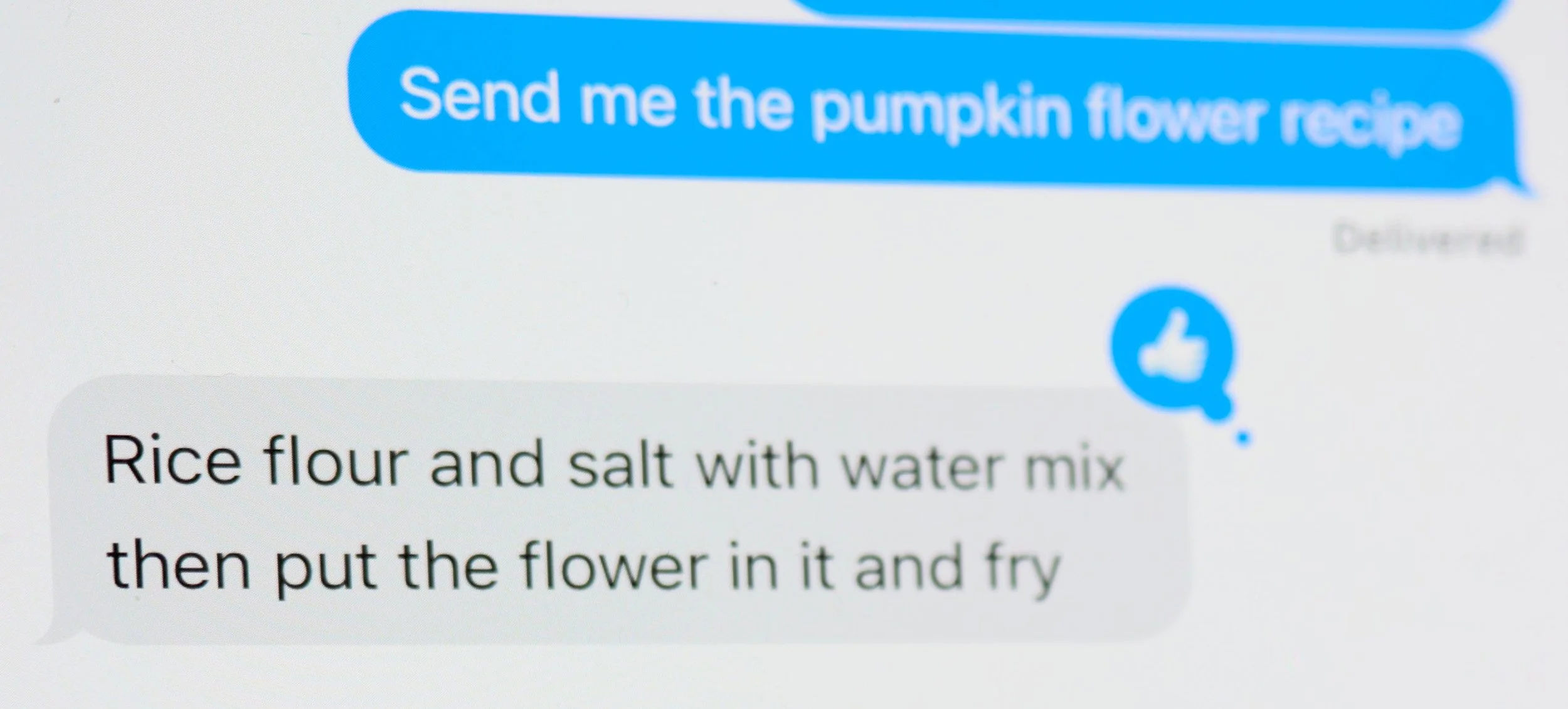

Snigdha prepares the batter by instinct: rice flour, a pinch of salt, a dusting of sugar, a scattering of nigella seeds that release their scent only when the oil warms. Sometimes she adds cornstarch to keep the fritters crisp for longer. Sometimes she adds poppy seeds because “some people like that.” But mostly, she doesn’t complicate things. The flowers themselves do the work. She removes the stamens, dips the blossoms in the pale batter, and lowers them into the shimmering surface of oil for two to three minutes. They emerge golden and delicate, with edges curled like lace.

What is the hold that this flower and a dish so simple that it barely feels like a recipe have on the Surs? As the founder of The Juggernaut, a media company that champions South Asian stories for the global diaspora, Snigdha’s world is split between her lived experience in New York City and the vividly crafted stories about the history, culture, and life of South Asians that she edits and publishes. The flowering of pumpkin flowers every summer is an annual event that grounds her in her ancestry and brings her two worlds together.

“Growing up in New York means all your food is global. In high school, many of my friends were Korean or Chinese, so I learned about hot pot, dumplings, and Peking duck early. My mom made Italian, Thai, and Chinese food too — I remember her wonton soup,” said Snigdha. “But the phooler bora is seasonal, which makes it even more precious. I look forward to it every year. It’s like this extra treat.”

RECIPE FOR PHOOLER BORA

Serves: 2–3

Prep time: 10 minutes

Cook time: 10 minutes

Total time: 20 minutes

Ingredients

8–10 fresh pumpkin flowers (male blossoms)

½ cup rice flour

1–2 tablespoons cornflour (optional; for extra crispiness)

½ teaspoon nigella seeds (kalonji)

1 pinch sugar

Salt to taste

Water, as needed

Oil for deep or shallow frying

Method

Rinse the pumpkin flowers gently and pat dry. Remove the stamen from inside each flower.

In a mixing bowl, combine the rice flour, cornflour (if using), nigella seeds, sugar, and salt.

Add water gradually to form a thin, smooth batter. The batter should be pourable and coat the flowers lightly.

Heat oil in a frying pan over medium to medium-high heat (about 170–180°C / 340–350°F).

Dip each flower into the batter, ensuring it is evenly coated, then carefully place it into the hot oil.

Fry for 2–3 minutes on each side, or until golden and crisp.

Remove and drain on paper towels.

Serve immediately. Traditionally eaten with moong dal and rice, but also works as a snack.

Words by Sneha Mehta. Images by Shravya Kag.

Special thanks to our partners.

ALSO ON GOYA

Neo-nomad cuisine of Central Asia | Terrence Manne