Inside Ladakh’s High-Altitude Kitchen

During her time in Ladakh, Komal Virwani gets acquainted with the intentional cuisine and ingredients that shape the region’s cuisine and finds that it is deeply rooted in their land, built around what grows in their high altitude terrain and what sustains them through long, harsh winters.

The kitchen of my homestay in the pottery village of Likir is already alive with movement. A round of dough rests on the counter, risen slightly from fermenting overnight. Tsewang, my host, presses it between her palms, flattening it into a thick disc with practiced hands. A faint toasty warmth fills the room as the flame flickers under the pan. This is khambir — the whole-wheat flatbread that anchors the Ladakhi breakfast table — in the making. Thick and nutty in flavour, it is traditionally cooked on a thap (multi-pot clay or stone stove) over an open fire, which gives it a firm crust and a smoky taste.

Beside the stove stands a tall wooden churn called a dongmo. Soon, steeped tea leaves meet salt and butter in this churn, stirred in steady circles until the brew turns a gentle pink. This was gur gur chai, the traditional butter tea that warms the body in the high-altitude cold. When Tsewang pours me a cup, she smiles and said, “Salt keeps us warm.”

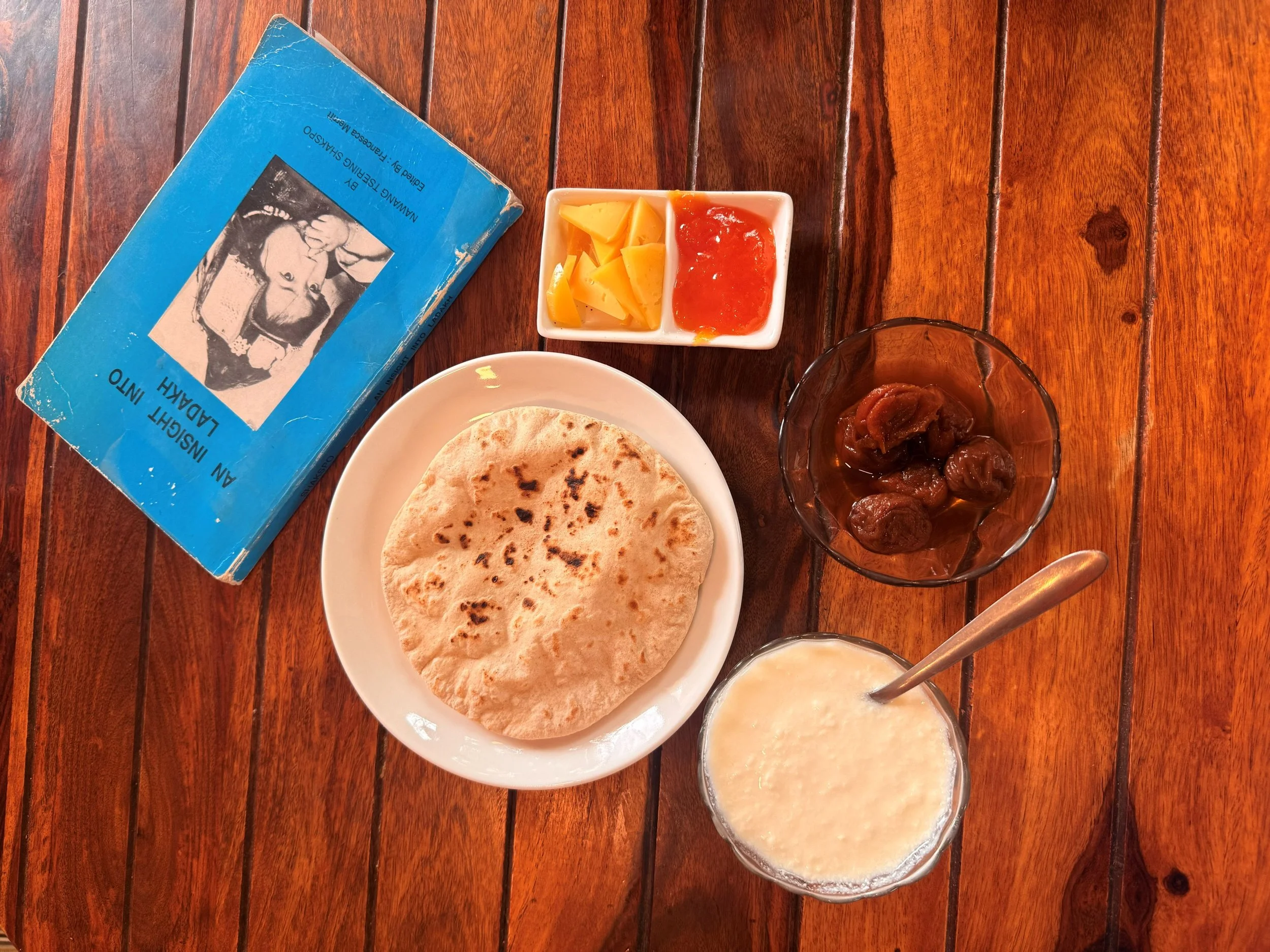

Ladakhi breakfast featuring khambir, yak cheese, apricot jam, curd and soaked apricot dessert phating.

The salty richness of the tea is still unfamiliar to my palate, but the khambir makes up for it. I tear off pieces, add a little jam, and the warm bread settles into me slowly. Nothing about it feels elaborate, yet everything in that breakfast had a purpose. That simple meal revealed something essential about this land, where geography decides what can grow and how people eat.

A Landscape That Shapes the Plate

Ladakh sits in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, where the air holds little moisture, the growing season lasts barely three months, and winter claims half the year. Yet people have lived here for centuries in this cold desert, building a cuisine around survival and self-sufficiency. Centuries of Buddhist influence, Central Asian trade, and mountain geography have shaped every recipe here.

Butter tea at Alchi Kitchen.

“Ladakhi cuisine is deeply rooted in our land, our climate, and our way of life. It’s simple yet soulful, built around what grows in our high altitude terrain and what sustains us through long, harsh winters,” said Nilza Wangmo of Alchi Kitchen, one of the few restaurants preserving traditional mountain recipes. “We use locally grown barley, apricots, wild herbs, and mountain greens, things that truly belong to our landscape. Every dish has a story, whether it’s about the harvest, the family table, or the connection between the food and the rhythm of nature. That’s what makes Ladakhi cuisine so different.” You see those stories most clearly in dishes like paba, made from roasted barley, wheat, and black peas. Once a staple across Ladakh, it came from a time when families depended on hardy grains that could survive short summers and long winters.

It’s the same story with khambir: the slow fermentation of khambir makes it easier to digest at high altitude, while its dense structure keeps it fresh for days. It fuels long hours of work in thin air and represents the quiet strength that defines life in these valleys.

Paba (made from roasted barley, wheat and black peas) with dip called tangtur.

A khambir vegetable sandwich.

A Centuries-Old Tradition

In villages, summer is a race to prepare for the cold. Families slice vegetables such as turnips, carrots, and cauliflower and lay them on bamboo trays across their flat mud rooftops, where the dry air and strong sun dehydrate them within days. Once dried, the vegetables are packed into cloth bags and stored in the warm kitchen loft for winter. This method, still common today, has roots in centuries of cold-desert food practices documented across the region. People who grew up in these landscapes remember when these dried stocks were essential for surviving the long winter months. Now, many families have better access to fresh vegetables in the colder months, thanks to improved road access and supplies coming in from the plains, but the habit of drying summer produce remains an important adaptation. In Ladakh, preservation is not a craft. It is continuity.

That sense of continuity lives on in skyu and chutagi, two of Ladakh’s most enduring dishes. Skyu is a rustic staple believed to be several centuries old. It begins with wheat dough rolled by hand into small cap-like shapes, then simmered in a broth of vegetables or meat. The result is a thick and deeply nourishing one-pot meal built for the cold mountain climate.

Skyu is a staple one pot meal with a broth of vegetables or meat.

Chutagi is a like a stew with hand-shaped pasta and vegetables.

Chutagi shares the same lineage but carries a more festive tone. Its story dates back to the Silk Route, when traders travelling through these high passes brought ideas of hand-shaped pasta. Ladakhis adapted the technique to their altitude and ingredients, shaping dough into bow ties or leaf-like forms and cooking it with root vegetables or meat.

When I tried both dishes during my time in Ladakh, Skyu felt like the kind of comfort one seeks after a long day, but it was chutagi that stayed with me. The pasta had a soft chew, the broth was warm, and the whole bowl felt like a small pocket of warmth on a cold Ladakhi afternoon.

Skyu and chutagi are now less common among younger generations, who often prefer faster, modern meals. The time and patience these traditional dishes demand have made them occasional treats, mostly cooked during winters, family gatherings, or festivals. Yet there is a quiet revival taking shape through homestays, local chefs, and restaurants like Alchi Kitchen. Young Ladakhis are rediscovering pride in their ancestral foods, seeing them as a living link to identity and home.

What the Seasons Allow

At Namza Dining in Leh, which restores lost Ladakhi recipes and dishes shaped by the Silk Route using locally sourced ingredients, I taste kabra sprinkled with sesame seeds and served with tingmo, a fluffy Tibetan steamed bread. The dish carried a subtle pungency that felt unmistakably of the mountains it came from.

"Kabra is an underrated Ladakhi dish that needs more representation," says Disket, co-founder of Namza Dining in Leh. "We savour the shoots instead of capers, and only have April and May to gather them. It's a true spring vegetable," she notes.

Kabra grows wild on Ladakh’s rocky slopes, its tender shoots foraged each spring before the plants bloom. Villagers soak them for days to draw out their natural bitterness.

Kabra (green one) with Tingmo (white one) at Namza Dining.

Wild apricots.

Come summer, Ladakh transforms into a landscape gilded with apricots. These trees, introduced centuries ago through Central Asian trade routes, have become central to the region's food culture and economy. Nothing goes to waste here. The fruit is eaten fresh, dried for winter, or soaked in water to make phating, a naturally sweet dessert enjoyed across Ladakh. The kernels yield chulli oil, with the sweet oil used for cooking and the bitter oil for skincare, medicine, and lamps. Enterprising young Ladakhis have built businesses around apricot products, turning ancestral knowledge into contemporary enterprise.

The Wild Berry of the Cold Desert

Among all the flavours I encountered in Ladakh, none surprised me more than seabuckthorn, or chharma. The shrubs grow wild along the Indus and Shyok rivers, their thorny branches heavy with small orange berries that glow like embers against the barren slopes. It almost feels like Ladakh’s wild answer to endurance, growing bright and defiant where almost nothing else can.

Seabuckthorn berries are sun-dried, pressed into juice or oil, and stored for winter.

Seabuckthorn juice at Alchi Kitchen.

I first tried sea buckthorn juice at Alchi Kitchen. It was citrusy and almost electric on the tongue, lifting my senses within seconds. I understood why locals reach for it when the altitude feels heavy. Rich in antioxidants and containing more vitamin C than oranges, these berries are nature’s way of helping the body adapt to life in the mountains.

In villages, women gather the berries carefully during late summer, when the branches are at their fullest. Once collected, the berries are sun-dried, pressed into juice or oil, and stored for winter. Today, sea buckthorn has grown beyond the kitchen. Its juice, jams, and teas fill shelves in Leh’s small shops, while the oil finds use in natural skincare.

Lessons from the High Desert

When I ask Jigmet what the world can learn from Ladakh’s food culture, she doesn’t hesitate. “Resilience and self-sustainability. That’s how locals really survived. You develop deep respect for how far you can go with your own local ingredients. Once we discovered this, we realized you don’t need to look anywhere else.”

Her words linger as I think back to the kitchens, orchards, and valleys that shaped every meal I tasted in Ladakh. In a world increasingly obsessed with the exotic and the imported, Ladakh offers a different lesson: that the most enduring food cultures are born not from abundance, but from deep attention to what the land offers, and the wisdom to make it enough.

Komal Virwani is a slow traveller and storyteller. Alongside her full-time remote job, she shares immersive personal narratives through her travel blog, The Local Pause.

ALSO ON GOYA

Neo-nomad cuisine of Central Asia | Terrence Manne