#1000Kitchens: Anjali Ganapathy Makes Gus-Gusay Payasa

At Goya, celebrating home cooks and recipes have always been at the heart of our work. Through our series, #1000Kitchens, we document recipes from kitchens across the country, building a living library of heirloom recipes that have been in the family for 3 generations or more. In this edition, Anjali Ganapathy shares the recipe for a Kodava gus-gusay payasa, one that belonged to her maternal great-grandmother Mathanda Chondamma Kariapa, and recreated through taste memory with her mother.

This season’s stories are produced in partnership with the Samagata Foundation—a non-profit that champions meaningful projects.

Anjali Ganapathy loads pandi onto thick slices of milk bread. It is early June in Bangalore, and her kitchen smells like slow-roasted spices. Two glasses of cold passionfruit juice gather beads, and we swipe every last bit of gravy off those floral plates.

“I started to feel guilty,” she says, moving between her Phillips mixer and two bowls of pre-soaked raw rice and jaggery on the counter. “Pig Out had given me so much: purpose, direction, happiness. I wanted to give back, but I couldn’t figure out how.”

For over a decade, Pig Out, Anjali’s culinary enterprise, has introduced Coorg cuisine to Bangalore through curated dining experiences, music festivals, Sunday markets and bar and restaurant pop-ups. She carried Kodava cuisine to far corners of the country, and abroad, always in conversation with the land and its culture.

For years, pandi curry was her anchor – a beloved dish, unmistakably Kodava in its flavour and colour, marked by the region’s distinctive kachampuli. A dish she describes as “an easy gateway into the cuisine.”

“Pig Out started from food memories,” she says, munching on a bowl of popcorn, freshly buttered, warm from the microwave. “I was trying to reach those memories of food as a kid -pickles, jams, those little things people had stopped making. I wanted those recipes – to try them out for myself, and to get people to taste them again. Of course, my mum was the first person I asked, then my aunts. And everyone shared so freely. It hasn’t happened to me yet where someone has said, no, this is my recipe.”

Now, almost a decade later, Anjali feels the ground shifting. “Finally, the market’s ready for something beyond pandi,” she says. “Desserts, subtle flavours – other things from the Kodava kitchen.” She strains the muslin cloth, and coconut milk streams through. Gus-gusay Payasa is made from rice, poppy seeds, coconut milk and jaggery. “Poppy seeds in Coorg cuisine is unusual. Perhaps it came in through wealthier households that travelled? This dish in itself is stunning; mellow, nutty, soothing. But in the right hands, it can transform into so many things – we’ve made gelato, panna cotta, even kheer.”

Gus-gusay payasa is a dessert she’d loved as a child but hadn’t found in years. “People got busy and they’ve stopped making it. It is time-consuming, and tedious,” she concedes. “You soak rice and poppy seeds overnight, blitz them together, then strain the milk through muslin three times or four times.” The payasa has disappeared from most household kitchens, but it is still served at wedding feasts, where caterers tend to skip the straining. “You’ll taste the rice grain and poppy seeds in your mouth – which is fine, but I prefer it the old way – I remember it thick and creamy, like a mousse.”

Standing in her kitchen, the old ways are finding new life. Jars line the shelves like a quiet archive. There’s an open jar of a lime ferment, charred and black, smelling irresistible. “Kaipulli paji,” she smiles as she digs a spoon out. Cooked down with spices until they turn almost inky, it tastes sweet and tangy, with a savoury finish that lingers. Next to it are cherry tomatoes and chow-chow, fermented with Brown Koji Boy’s hot sauce, and Gonzo’s mustard. Her kitchen is an ongoing conversation between tradition and experiment.

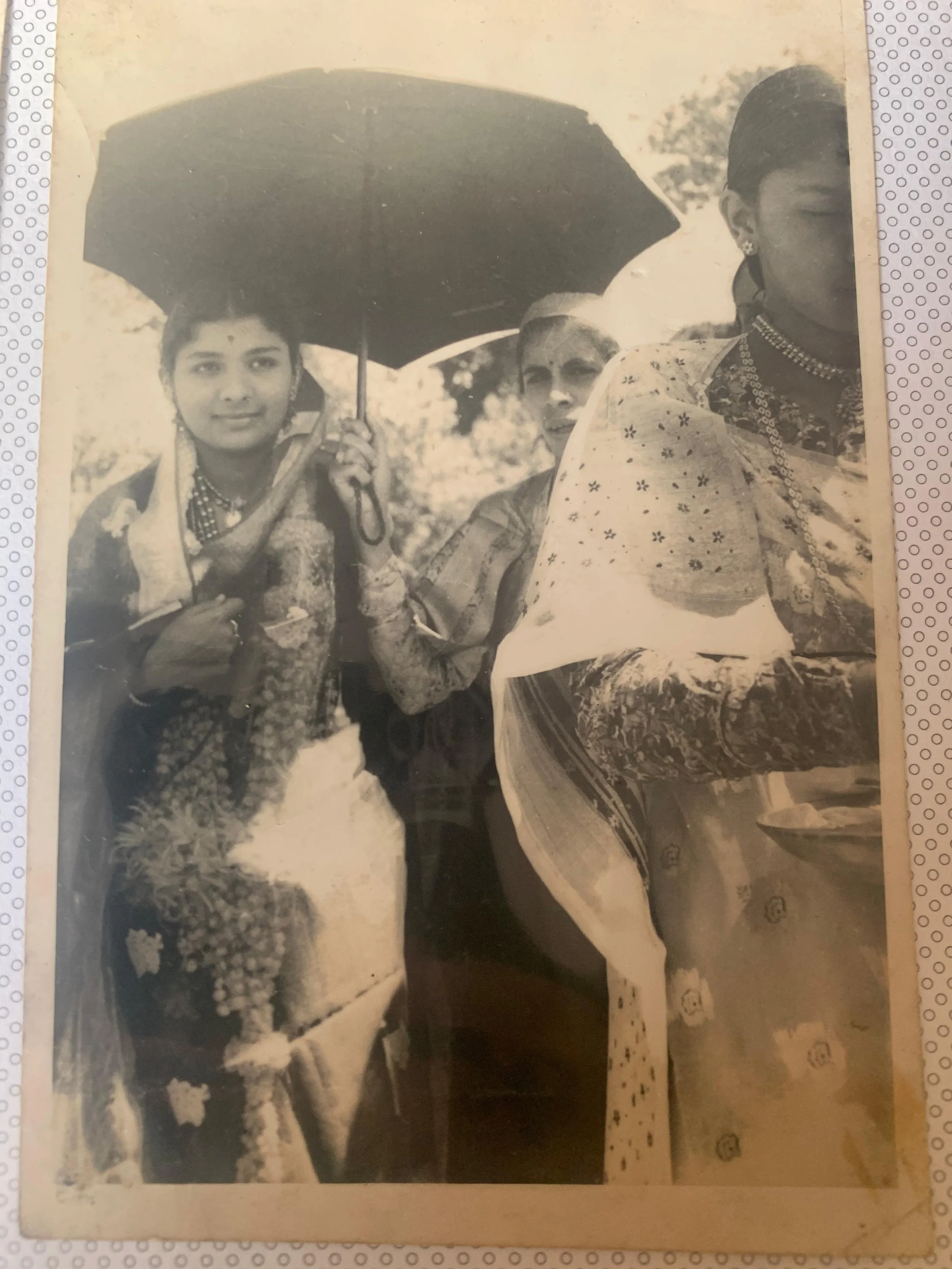

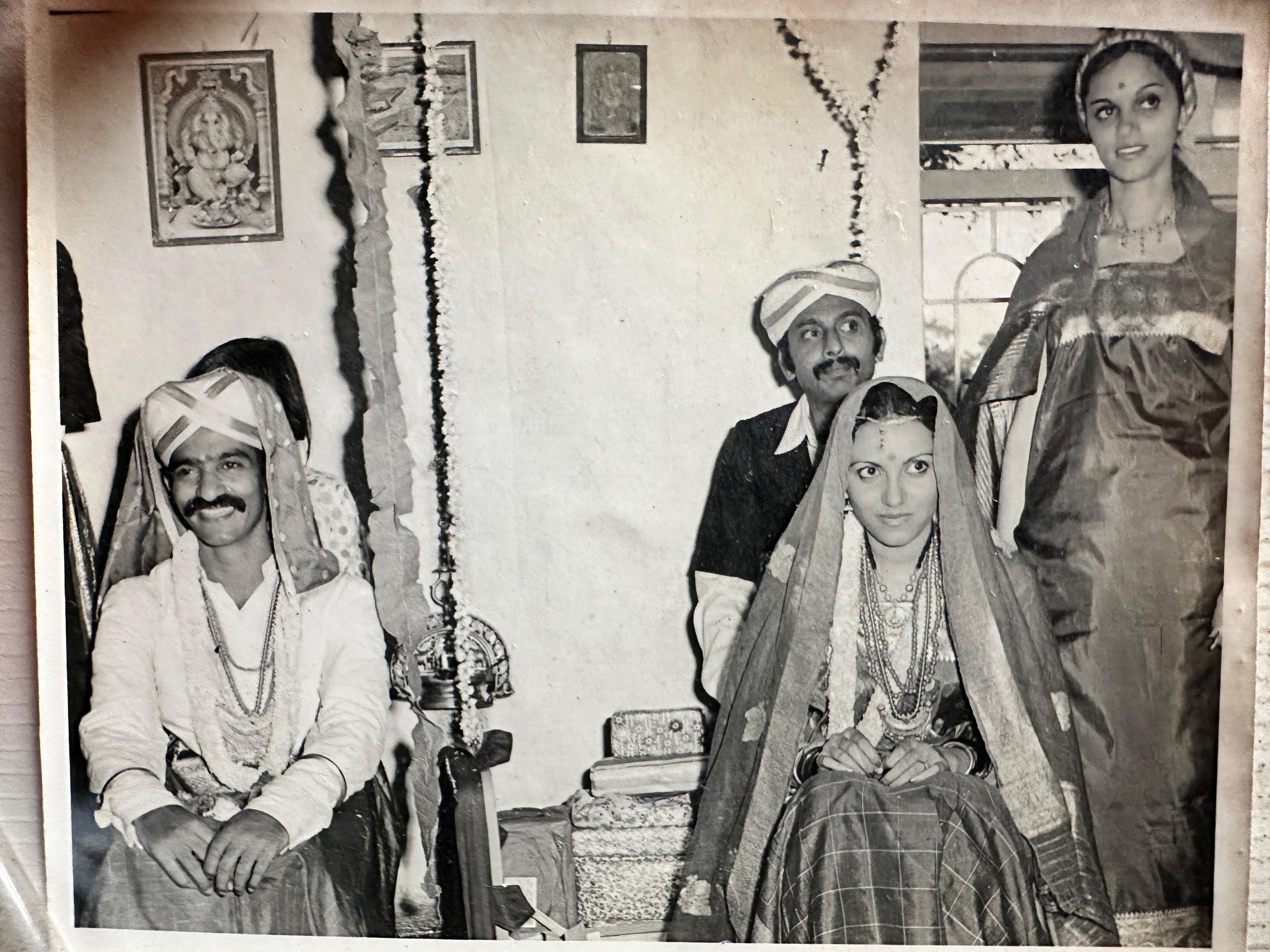

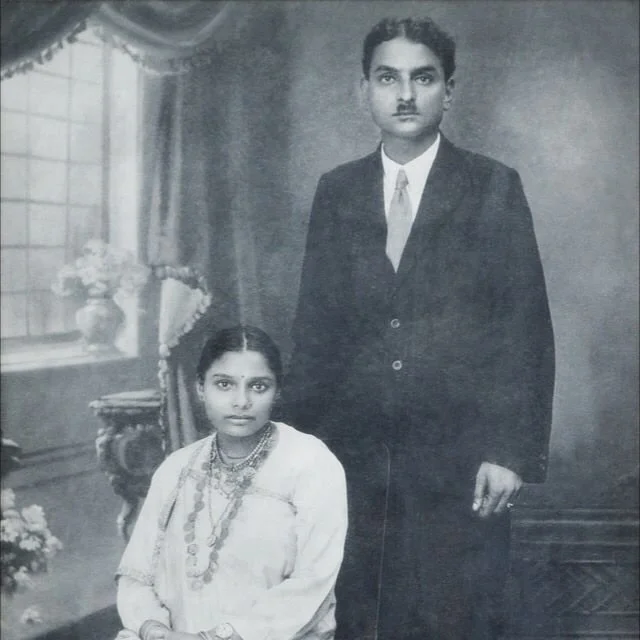

Above: Anjali’s great grandmother Mathanda Chondamma Kariapa (on her mother’s side) and her husband, Mathanda M Kariapa, photographed at a studio in Mumbai in the 1920s. Below: photographs of Anjali’s mother and grandmother.

Anjali grew up spending her summers in Coorg. “My gran was the oldest of her siblings,” she recalls. “Her house was always open – there was a constant stream of people, food, and chatter. In farming communities, you went to each other’s homes with produce you had harvested from your land – oranges, mangoes, a sack of rice. Everyone contributed something to the meal. And in that circle, you knew who made the best trifle pudding, who was famous for their chutneys. It all ended up on the table. Even the simplest rice or chutney were made with such care and attention.” Her grandmother had cows, and Anjali remembers coffee that tasted like condensed milk, thick and sweet. “Everything was fresh, wholesome. Nothing was ever rushed,” she says.

She remembers when she finally decided to try making gus-gusay payasa herself. “I hounded everyone for the recipe quite shamelessly! Gimme gimme gimme, tell tell tell!” she laughs. “Mum and I pieced it together from memory. And one of my aunts described it vividly – her whole face changed: she said, ‘You can eat it like ice cream.’ That was my roadmap.”

It takes patience. “You strain it three times until the water turns clear. Then you heat ghee and slowly reduce the mixture with coconut milk and jaggery. Keep stirring. You’ve got to watch it because it clumps easily. It’s a simple recipe with very few ingredients, but it needs time and a watchful eye. I actually enjoy zoning out as I squeeze that muslin cloth. I find it meditative.”

With practice, she’s learned what can be adjusted. “Mum says put everything together and combine, but I prefer to grind and strain the coconut separately. It’s coarser and doesn’t go through muslin well. These things you only figure out by doing it over and over again.”

When it’s done, the payasa is thick, buttery, and deeply comforting. “It tastes like ice cream, but softer. Buttery, creamy, mellow, and nutty,” she says. “Sweet, but full-bodied.”

She pauses, pouring herself another sip of passionfruit juice. “I started Pig Out to share Coorg food,” she says. “Now I feel responsible for it. I need people to see it, love it, understand it the way I did.”

Along the way, her curiosity deepened into awareness – about seasonality, and what was quietly vanishing from the table. “I was building a knowledge bank, and then I started noticing what wasn’t showing up anymore – wild mangoes, wild fruits, bamboo shoots, mushrooms, wild herbs, medicinal plants. Things that were once ordinary,” she says.

At a recent Pig Out X Masque pop-up, the conversations were thoughtful, searching beneath the surface. “People asked about micro-climatic changes, about the land and the food systems,” she says. Newer stories from Coorg tell of land conversion, disappearing wetlands, the microclimates shifting. “Even in my own home, we notice it,” she says. “Where is the koilameen, the paddy fish we used in curries, pickles, and cutlets? I started feeling desperate. I had to do something.”

The woman who cooks for her family seems tuned to the land in a way most have forgotten. “She would tell me, after a thunderstorm, mushrooms will appear in that particular spot. And sure enough, the next morning, they’re there,” Anjali smiles. “It can seem mysterious because there are no clear answers.”

“This is where my heart is right now – using food as a medium to talk about our lands, to inform people.” The next chapter to her work is already unfolding. Anjali shows us early drafts of a project that has been two years in the making: the Coorg Conservation Collective, a organisation that looks to build a sustainable future for the region, rooted in ecological restoration and regeneration.

Her kitchen smells faintly of ghee and toasted poppy seeds. Outside, the afternoon is warm and still, birdsong floats in through the window. The last of the pandi curry cools in the corner, black limes age on the shelf, and bowls of gus-gusay payasa are steaming on the table, waiting to be eaten.

RECIPE FOR GUS-GUSAY PAYASA

Note: Serves up to 8 dessert bowls. At the end of the cook, the quantity of payasa will have doubled, so adjust accordingly.

Ingredients

½ cup rice

1 cup poppy seeds

3 tbsp ghee

1 cup milk

1 cup coconut milk

½ tsp cardamom powder

Sugar or jaggery, to taste

7-8 ghee fried raisins & cashew

3 tbsp ghee

Method

Soak rice and poppy seeds together in a 1:2 ratio. Any white rice will do. This recipe uses jeerige sanna (jeera samba).

Wash and soak rice and poppy for a minimum of two hours. I prefer to leave it overnight; this ensures the rice has softened nicely, and it counters the more stubborn variety of rice. If the weather is very humid where you are, leave it in the fridge, to avoid potential souring.

Add water, grind to fine paste and extract the milk, by straining through a muslin cloth. Set the extract aside and repeat process twice more, adding water to the leftover grains, then grinding and straining.

In a pan, heat ghee, add the extracted rice-poppy milk and keep stirring with a whisk or spoon till ghee is fully emulsified. Gradually add the milk and coconut milk, and a pinch of cardamom, and jaggery or sugar to sweeten it.

Keep stirring to avoid lumps. Turn off the gas once it thickens and is viscous (it should leave a thick coating on a spoon).

Garnish with ghee-fried raisins and cashew.

This can be consumed cold too.

Words by Anisha Oommen. Photographs by Terrence Manne. Artwork by Antara Raman.

Special thanks to our partners.

ALSO ON GOYA

Neo-nomad cuisine at its finest | Terrence Manne