#1000Kitchens: Kadambari Tandel Cooks a 100-year-old Koli Recipe for Dangra-cha Kanji

At Goya, celebrating home cooks and recipes have always been at the heart of our work. Through our series, #1000Kitchens, we document recipes from kitchens across the country, building a living library of heirloom recipes that have been in the family for 3 generations or more. In this edition, Koli artist-activist couple Parag and Kadambari Tandel talk to Yoshita Sengupta about vanishing communities, ecology, traditions and recipes while cooking up dangra-cha kanji, a pumpkin-coconut-prawn stew cooked by their ancestors for centuries.

This season’s stories are produced in partnership with the Samagata Foundation—a non-profit that champions meaningful projects.

It is 10 am on a Tuesday. Far from home, I sit in the car staring at a partially broken wall and the railway tracks on the other side. The tarmac is too narrow for the car doors to open fully, let alone attempt a U-turn. In the rear-view mirror are a few residents of Chendani Koliwada quietly watching, mostly out of concern — no honking, sledging or judgment. As I employ all my skills to reverse and wriggle out of the lane, my mind tries to recall how it forgot the make and nature of the city’s old settlements that it navigated for over three decades before mobile applications colonised it entirely.

Minutes later, I settle into the quiet, modest third-floor studio apartment in one of these old settlements. My hosts are Parag and Kadambari Tandel, alumni of Sir JJ School of Arts, and an eminent couple in their own right. Kadambari is an artist-activist-archivist. Parag is a Maharashtra State award-winner, artist and visual auto-ethnographer. The Tandels are Kolis, considered to be Mumbai’s indigenous community.

My co-host rues his presence at our interaction. “She insisted. I don’t know why,” he says. She, [Kadambari] responds with a smile, continuing to rinse the locally caught, rust-red prawns that she procured when we were deftly retreating the lane that has been home to several generations of the couple’s families. The prawns will star in today’s meal.

Kadambari Tandel is an artist, activist and archivist.

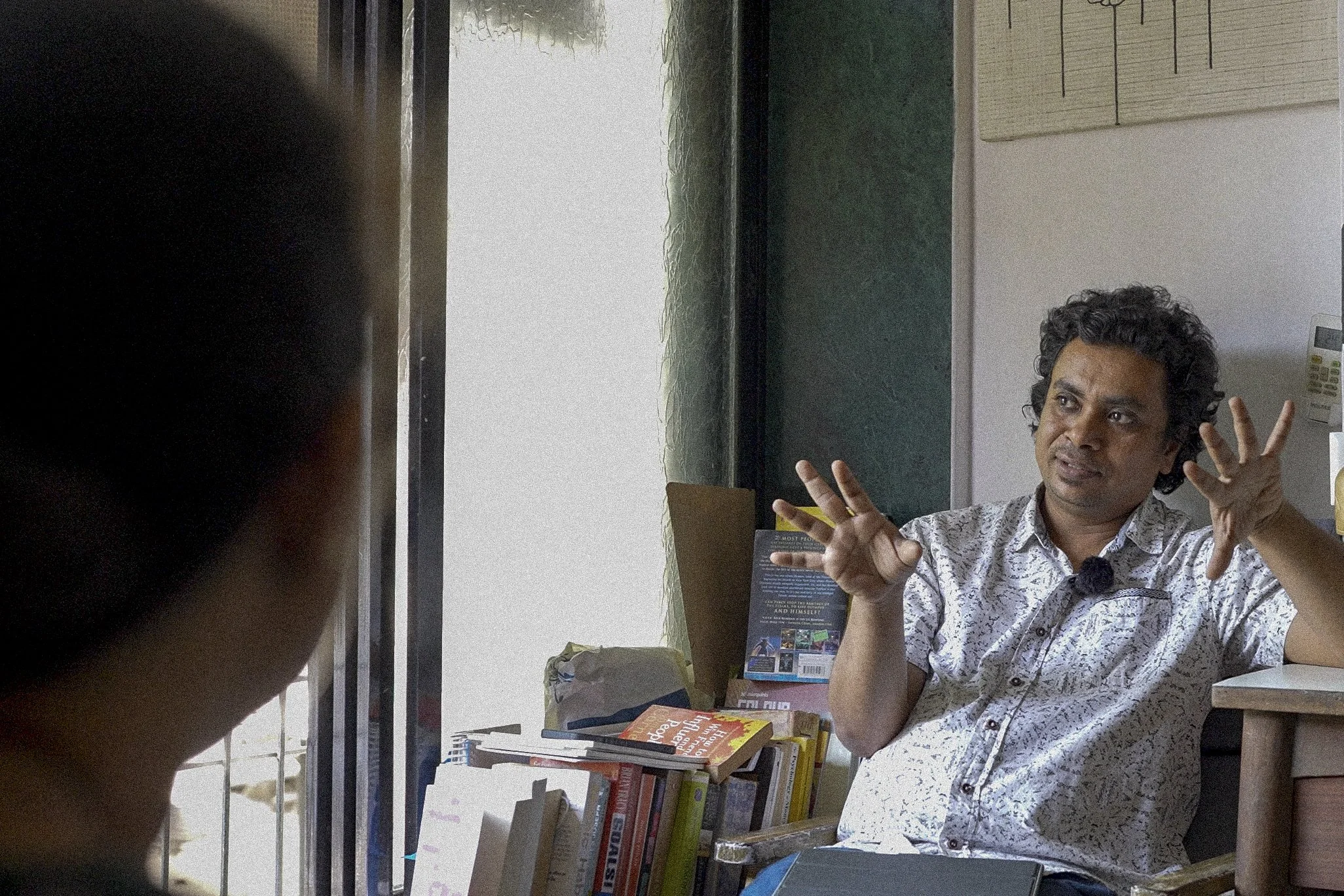

Parag Tandel is an artist and visual auto-ethnographer

Parag may be reluctant to be present, but he is looking forward to the meal. He admits to finding solace in this very prawn vata (an old Mumbai way of measuring fish quantities) that allows for a fascinating and customary round of haggling. “At least I get to eat this dish on a Tuesday. She [Kadambari] doesn’t eat fish or non-vegetarian food on certain days,” he says. This lunch is thus a rare treat. “These structured practices of various religions have been layered on top of the practices and beliefs native to our people. I don’t practice any of this, but she does. So…,” he shrugs.

It takes only a few minutes to pick up on the elevated social and cultural consciousness of the couple, especially of Parag, whose passion leaps at you, even as he tries to exercise restraint.

I move closer to the kitchen and lean against the chest-high refrigerator, and strike up a light but fascinating conversation with Kadambari about dangra-cha kanji. This dish has been cooked by multiple generations of her family using ingredients and techniques that, she believes, represent the culinary traditions of her land and people. “The dish uses limited ingredients most of which are indigenous to the land — pumpkin, coconut, rice flour, kokum, hing (asafoetida), turmeric and the green chillies and garlic,” she says, which are perhaps the only ingredients that may have found their way into the recipe a hundred or so years ago.

Kadambari points to the hero ingredient, the dried seed of the bafli shrub, which is found growing in the jungles around the community settlements. “Of course, the jungles have been replaced by concrete structures so it can be challenging to find, but one can still find it in the jungles of Karjat. Women sell them in our community markets,” she explains. The bafli seeds are added to most traditional kanji (stew) preparations and lend the dish a subtle but distinct aftertaste. The seeds aid digestion and have medicinal properties, Kadambari says, but she also warns against overusing them: “Two to three seeds in a pot of kanji is more than sufficient.”

She also points out that the preparation uses no oil: “The dish has only natural fat from the coconut.”

Fiber, good fat, iron, antioxidants, white protein, and native herbs, fruits, and spices that help with digestion, blood sugar, and heart health — as Kadambari breaks down the components of what she keeps referring to as the family’s comfort food, it starts to dawn on us that comfort, in this case, likely has meanings beyond nostalgia and familiarity.

Clearly, the ancestors, centuries ago and despite their limited means, knew what they were doing. “At times growing up, we’d get to eat this when they [grandmother or mother] would be running late or needed a shortcut dish.” The dish, with the addition of prawn or dried bombil, is also made during Pitra Paksha, a 16-day lunar cycle to honor the ancestors. Much like in several coastal communities across the country, the catch from the sea is classified as vegetarian.

Kadambari expertly maneuvers the tiny space, ticking off steps of the recipe, while also addressing my curiosity about the significance and context of the dish in her life: “It is easy. It is affordable. It is nutritious. It is a complete meal in itself. Pumpkin is always available these days. If it’s not, it can be replaced with bottle gourd or even drumsticks. You can choose to skip prawns entirely. In certain seasons or when it needs to be made immediately, dried bombil soaked in hot water can replace the prawns. It’s the community’s go-to food.”

Kadambari is perhaps thrown off momentarily when I ask her if the community has a tradition of eating dal. “Yeah…No. We don’t. We do eat moong dal sometimes,” she responds. This is likely because lentils were neither native to the forests and oceans near the Koli community settlements nor grown in the region's fields.

Is this then the Koli equivalent of dal or kadhi chawal? “Yes, yes! When we want to fix a quick meal with the ingredients we typically have at home, we make kanji.”

By this time, the kanji is ready and left covered to allow the flavours to settle in.

We settle in for a conversation where Kadambari and Parag give us the wider cultural context of the community using examples from their project of documenting and reviving Koli food. As Parag talks about reviving nittal, a monsoon dish similar to dangra-cha kanji but made with dried bombil and without any vegetables, we try to understand how and why the recipes vanish, to begin with.

Each koliwada, even each household within a community, has recipes of their own that remain within, they aren’t written or documented. Several have faded away with time. A lot of the recipes, they explain, include ingredients that grew near the community back in the day. In the case of some recipes, with concretisation, those ingredients become hard to find and families eventually stop making them.

The way the community structures operate and the absence of formal cultural exchange or conversations is another reason for the loss. “Typically, marriages happen between people of two different koliwadas, in which case you often learn or cook recipes of the koliwada you marry into or live in,” Parag explains. That, if at all, is the only way recipes travel, Kadambari adds. But in several cases, that can also lead to some recipes vanishing from the repertoire of a generation. In the case of the kolis, where the cuisine is native to a small area or even a household, recipes fading from the memory of one generation is all it sometimes takes for them to vanish.

By this time, the juices of the prawns are adequately infused in the kanji. Kadambari serves it to us on a steel plate. We sit on the floor, cross-legged, dipping our hands into the rice and kanji. As I near the end of our meal, chomping on the shells and tails of the prawns, we realize that, unlike the ubiquitous dal chawal, the possibility of the kanji I just devoured vanishing from culinary tradition is more real than we may like it to be.

KADAMBARI TANDEL’S RECIPE FOR DANGRA-CHA KANJI

Ingredients

500 g pumpkin aka dangar [the variant with the hard, green skin]

1 freshly grated coconut

4 tbsp rice flour

1 tsp turmeric powder

½ tsp asafoetida

4 light green chillies, stems removed

2-3 dark green chillies, stems removed

3-4 pieces bafli

5 large or 8-9 regular-sized garlic cloves

5-6 pieces fresh kokum

Salt to taste

Water

200 g prawn (recommended but optional) with tail and a few heads, for more flavour.

Method

Leave kokum pieces to soak in a small bowl of hot water. Squeeze and extract a runny paste. Discard the skin.

Peel the pumpkin and chop it in large 2-3 inch-sized chunks. Pressure-cook the pumpkin chunks with half a teaspoon of turmeric and salt till you hear the whistle go off thrice. Leave the cooker with the lid closed for at least 20 minutes.

Use a glass of water to grind the grated coconut, bafli, garlic cloves, asafoetida, light and dark green chillies to a thick paste. Pass the paste through a sieve and extract thick coconut milk (first press). Squeeze the coconut mixture in the sieve to ensure you get all the milk you can.

Grind the coconut scrapings/ pulp left in the sieve using another glass of water. Strain and squeeze the mix to extract a glass of thin coconut milk (second press).

In a bowl, add half a spoon of rice flour and slowly stir in water by the teaspoon to form a thick paste. Add the remaining rice flour and water as you continue to stir ensuring the paste is runny with no lumps.

If using prawns, add them to the water left over in the cooker after removing the pumpkin chunks and give them a quick boil.

Add the pumpkin chunks, the second press (thin) of the coconut milk and a glass of water to a large pot. Place the pot on a slow burner and gently stir the pot as the mixture starts to heat up. Low heat, used through the entire cooking process, is key to ensuring the coconut milk does not split. Add the second press of the coconut milk as you continue to stir. Leave the pot to simmer for a couple of minutes before gently stirring in the rice flour paste, followed by the remaining half a teaspoon of turmeric powder.

As the mixture comes to a slow boil and starts to thicken, slowly add the prawns along with the water it was boiled in.

Another three to four minutes later, drizzle the kokum paste into the pot. Be gentle with this step; sour kokum can split the coconut milk if it’s not stirred in gently or if the burner flame is too high.

Let the mix come to a final boil; another 2-3 minutes. Taste and adjust salt, if needed.

Turn off the heat, cover the pot with a lid and let it rest for at least 15 minutes.

Tips: The locally-found, small or medium-sized, rust/ orange prawns work best with the dish. The consistency of the dish typically resembles a more viscous dahi kadhi than a Kerala Stew or Sambhar. You can adjust the consistency according to your preference by adding more water or reducing the rice flour quantity. You can adjust the kokum paste and green chilli quantities based on how much tang and heat you prefer.

Words by Yoshita Sengupta. Images by Nachiket Pimprikar. Art by Anjali Kamat.

Special thanks to our partners.

ALSO ON GOYA