Bengal Famine on Film: A Feminine Lens

In post-famine films, the images of women have been employed to present two aspects of it, one to personify and one to glorify. Kratika Khatri explores this duality in context of films of two pioneers of Bengali cinema — Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray.

Notions of nourishment and kitchens through the ages have been symbolically tied to women.

However, in times of scarcity, when the inherent purpose of the kitchen is disrupted, the imagined constructs of all-sacrificing universal motherhood also come under scrutiny. After the Bengal famine of 1943-44, post-famine productions in films, literature, art and theatre dealt with these themes with great sensitivity.

The Bengal Famine of 1943-44 was a watershed event that concluded with more than three million recorded deaths. While it was never officially declared a ‘famine’, it was a consequence of a series of events unfolding at the height of World War II. Japan’s invasion of Burma in January 1942 caused a chain reaction in provincial Bengal starting with the disruption of rice supply. As a de facto ally of the British Empire, Bengal was a major war front for the Allied forces. The war cabinet in England formulated preventative strategies to counter a possible attack on the Allied ground of the undivided Bengal. By March 1942, denial policies of scorched earth were placed into effect to remove surplus rice stocks and boats from rural Bengal to stave off the enemy forces. This left thousands without means of a livelihood.

Compounding the crisis was a cyclone in October 1942, which destroyed vast paddy fields in Medinipur. Inflation and panic hoarding became natural outcomes. “Straight in front of them stood famine” : although the quote from the novel Anandamath by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay was written in reference to the famine of 1770, the circumstances in 1943 were analogous and still relevant.

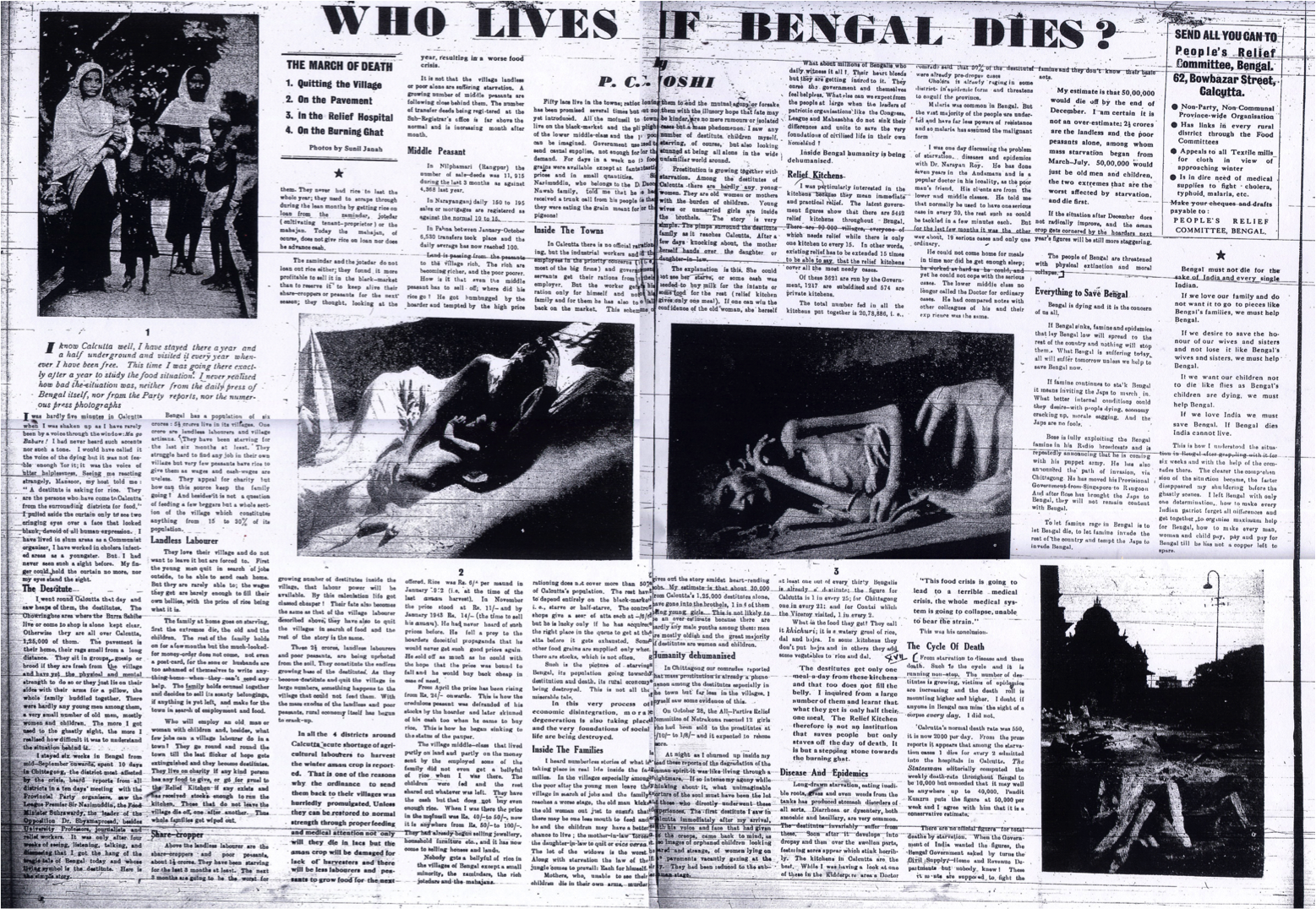

A news article about the Bengal famine.

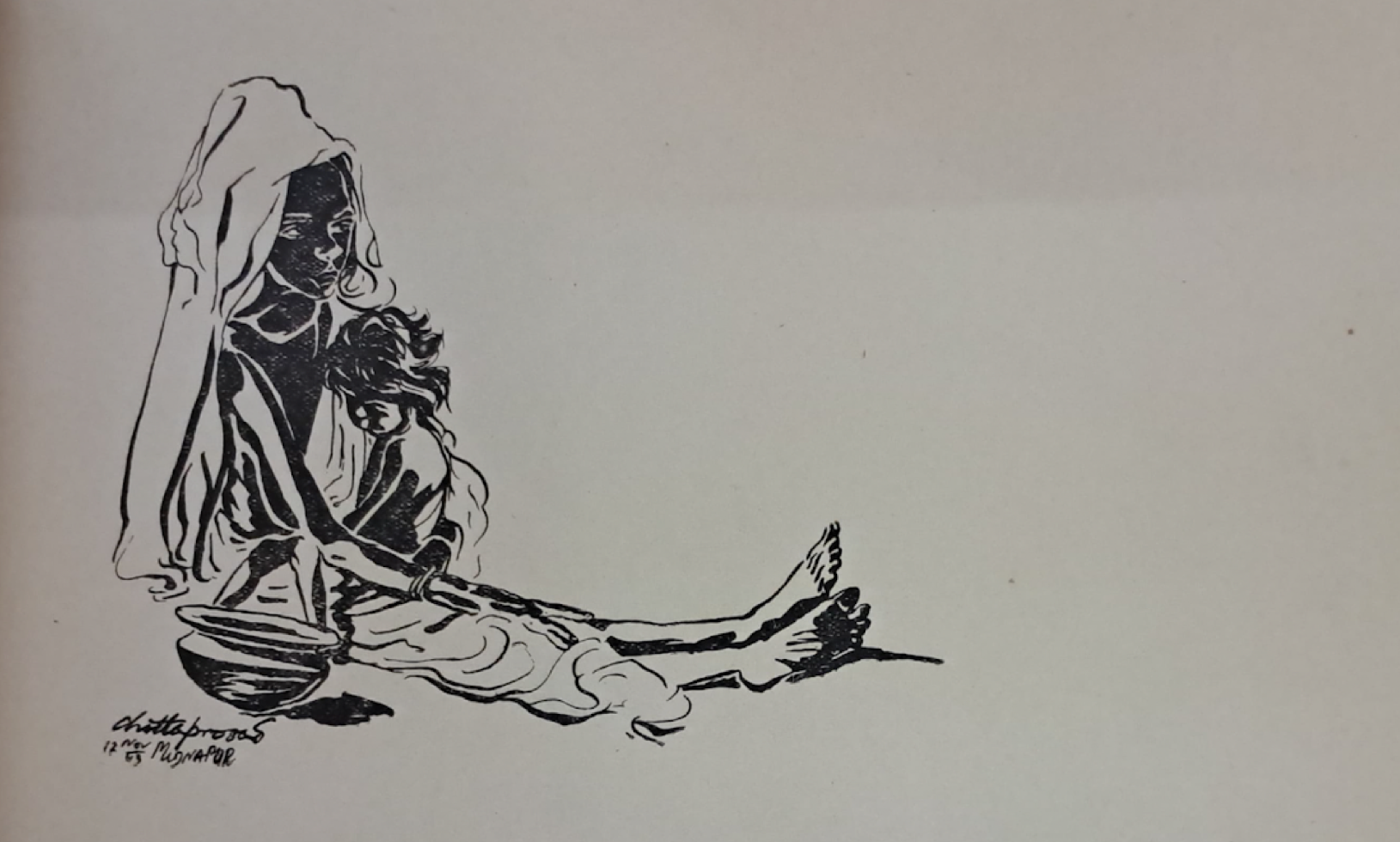

The opening of Anandamath describes a Bengal ravaged by hunger, starvation and diseases, where morals are lost and social disintegration seems inevitable. The famine narratives and imagery of Anandamath were evoked again in 1943-44 by artists Zainul Abedin, Somnath Hore, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya and photographer Sunil Janah documenting the on-ground realities. Images of mother and child, mass migration and never-ending queues at aid kitchens/ration shops were relentlessly reproduced; and continued in the post-famine production.

Even though the crisis ended in 1944, residues of the trauma persisted as traces in mediums such as films, allegories, songs, literature and even recipes. We look at three such Bengali films — Baishey Shravana (1960) and Akaler Sandhaney (1980) by Mrinal Sen and Ashani Sanket (1973) by Satyajit Ray. The representation of women in these films is testimonial to the loss of virtues and morals in dire straits. ‘Women, who have customarily had inferior access to the food and medical resources of the family in conditions of alimentary normalcy, experience a heightening of such disparities in the eventuality of famine,’ writes Parama Roy in the book Women of India: Colonial and Post-Colonial Periods.

Baishey Shravana (Wedding Day) is a tragic romance unfolding in an early famine setting in rural Bengal. Revolving around the two protagonists, Priyanath and Malati, the film is a brilliant and intimate character study of the effects of famine by Mrinal Sen. The film follows the newlywed couple in celebrations. When Priyanath’s mother passes away while the couple is absent, he becomes riddled with guilt and helplessness.

Baishey Shravana (Wedding Day) is a tragic romance unfolding in an early famine setting in rural Bengal.

Witnessing the shift in her husband’s demeanour, Malati’s persona grows more serious and helpless. Malati saving the leftover rice from Priyanath’s meal is a pivotal scene depicting the first sign of famine materialising. Priyanath’s candid ignorance is most evident in his dialogue “You finished eating already?” His changed attitude left Malati exhausted and without a support system, finally driving her to take her own life.

The beauty of Baishey Shravana lies in its manner of depicting famine and its effects in one’s personal space without any grotesqueness. Visual indicators of the famine — inflation, migration and epidemics/diseases — existing throughout the film are merely muted. Sen encapsulates the severity of the situation in the development of these characters.

Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder) based on Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s eponymous novel, exposes a gendered experience of famine with recurring themes of hunger and lust. The film revolves around a Brahmin couple, Gangacharan and Ananga, settled in rural Bengal. The couple enjoy being the only Brahmins in the village initially; however as the effects of the famine become more pronounced, their caste entitlement is shattered. The privilege of plenty that Gangacharan once enjoyed is lost and his kitchen, like every other in the village, also becomes barren.

In the film, the kitchen is Ananga’s primary space. In contrast to occupying that space, she is never seen consuming any food, only selflessly cooking for her husband and fanning him as he eats. Ananga’s character embodies ideals of universal motherhood, an image torn apart in the documentation of the famine. Caste and class dynamics surface as Ananga joins other village women in foraging for items like slugs and tubers — foods typically avoided by ‘upper caste’ individuals under ordinary circumstances.

The subplot of Chutki underscores the exploitation of women during the famine. She is pursued by an outcast, who offers her rice in exchange for sexual advancements. Initially disgusted, she later succumbs to her hunger and the man’s devious nature. This scene highlights the discourse of representation — Chutki in the red saree and her resemblance with the goddess of food, Annapurna. Etymologically, Anna, means food and purna means complete, and Annapurna is the giver of nourishment and an everlasting source of food. The choice of colour of Chutki’s saree in this scene collating her with Annapurna seems like an apparent move on Ray’s part.

In the context of the afterlife of the famine, Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhaney (In Search of Famine) is a film within a film dealing with ideas of memory, trauma and shame.

The plot unravels as a film crew from Calcutta moves to a village to shoot a movie searching and re-constructing glimpses of the famine some forty years after the actual event. The opening scene depicts crew cars entering the village as onlookers curiously stand on the side. A man standing by exclaims, “The Babus have come in search of the famine; the famine is all over us.” He describes a Babu’s/outsider’s attempt to perceive suffering that still persisted in the most vulnerable areas. The woman holding an emaciated child next to the man delivering the dialogue stands in plain sight, yet shadowed. Sen deliberately places this image here to re-construct memories of the famine. This exercise of recreating glimpses of hunger referring to the documentation of the 1943-44 famine is consistent throughout the film with a special focus on mother and child.

Akaler Sandhaney (In Search of Famine) is a film within a film about a crew from Calcutta moves to a village to shoot a movie searching and re-constructing glimpses of the famine forty years after the actual event.

The film’s central discourse on shame is narrated as the protagonist — the movie director searches for a woman to play the role of a beshya (prostitute) in his movie. Dialogues like “What do these city/Calcutta contractors think, that for some money we would give our daughters to them,” foreground the lingering sense of shame. The men now frown on the idea of letting the women even play the role of a beshya when many families survived by selling the same daughters/sisters/wives during the worst of times. The use of terms like ‘contractors’ and ‘money’ juxtaposes the realities of the 1943-44 famine in front of these men who are unable to come to terms with it still forty years later. The exponential increase in sex trade and prostitution in Bengal in 1943-44 is well recorded, but to speak of it was almost taboo.

In all documentation and post-famine productions, images of women have been employed to present two aspects of the famine, to personify and to glorify. In personification, famine takes the form of a famished woman with hollow eyes and saggy breasts. In the novel, Witch Hunt, by the celebrated Indian writer, Mahasweta Devi, she is a “terrible figure of a dreadful female, dark and completely naked, flying atop a blood-red cloud saying ‘I’m famine’....she was indeed a witch.” On the other hand, Annapurna in her red saree and spoonful of rice, dispels the image of scarcity. This duality persisted in post-famine narratives is the paradox of scarcity and maternal sacrifice.

Kratika Khatri is a researcher trained as an art historian exploring the intersections of food, art and material culture in South Asia.

ALSO ON GOYA