Kasoundé & the Rules of Modern-Day Colonialism

If you go far back enough, everything comes from somewhere else. Nisha Sudarsanam looks at colonialism and the peculiar cycle of borrowed references between the oppressor and colonised, giving rise to a unique, hybrid cuisine.

Who owns the right to name a recipe? Where does the line between innovation, and co-opting lie? In the first (and only) two episodes of the Reply All podcast titled The Test Kitchen, they reveal fresh horrors of how recipes were selected at Bon Appétit, a popular American food and lifestyle brand owned by Condé Nast. Granted, the podcast itself is now mired in problematic context. But it also describes legitimate instances of white decision-makers making egregious decisions on non-European recipes, such as the dumbing down of a 4-chilli sauce recipe for pork tamales, and reassigning the recipe for soup dumplings to a white writer instead of the Asian writer who proposed it. All of this to make recipes more palatable for a mostly white, and mostly millennial, audience. Does this represent modern-day colonialism? And how do we condemn generations of food appropriation, perpetuated by colonialism, while also acknowledging that that this very appropriation played a critical role in defining authenticity within the cuisine it infiltrated?

As a woman who grew up in India, I am the child of one kind of colonialism — British colonialism. And as a brown woman living in America, I now struggle with a different kind of colonialism. Distinguishing what is authentic versus what is stolen in the culture that surrounds me — from the books I read, the music I listen to, the clothes I wear, the phrases I utter, and even the food I eat — is near-impossible. The last year has led me to delve further into the origin of authenticity in my own life.

Stephen Fry once remarked, “History is not the story of strangers, aliens from another realm; it is the story of us, had we been born a little earlier. History is memory.” My own memory lies in India, and were I to go back to 19th-century India, where 1200 British civil servants arrived to build an administrative machine that would come to exploit a subcontinent of 200 million, I would find, enmeshed in the larger monumental story of British rule in India, the significantly more mundane story of the recipes that were created for, by, in and adjacent to these British households.

These households created a cottage industry for a class of cookbooks and instructional manuals written by British women (and men) on how to run a household in India. Cookbooks reflect the aspirational desires of a culture at a given point in time. They reflect us reaching for a better version of ourselves. If aliens were to understand the human race through a study of bestselling cookbooks on Amazon today, they would probably believe that humanity’s ambitions were centred on being skinny and healthy. We want to believe that a ketogenic-paleo-vegan diet will bring us closer to that ideal body, and more importantly, make us feel a little better about ourselves. 19th-century India is no different. As an alien spying on the cookbooks of that time, I can only conclude that British housewives felt out of their depth, and frankly lost, in these foreign lands. Ironically, for a people that travelled thousands of miles to dominate another race, they were remarkably ill-equipped for the daily intricacies of building a home elsewhere. Their cookbooks served as a guide to this end, outlining very specific instructions to help prevail over their native servants. An example of this is Flora Steele and Grace Gardiner’s popular 45-chapter tome, The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook, which is filled not just with recipes, but with precise guidelines on how to run a household in India, what cutlery to buy, how to manage weekly expenses on provisions, and other processes that were likened to running the Empire.

And when I say guidelines, I mean spectacularly racist, condescending and patronising tips on how to manipulate native help, who are treated (and considered) less than human. Some management tactics can even be viewed through the lens of modern-day capitalism, where corporations (or restaurants) hire low-wage workers on minimum wage, but retain them with promises of pitiful overtime pay, tips and bonuses (now clearly categorised a racist practice, when first introduced in America).

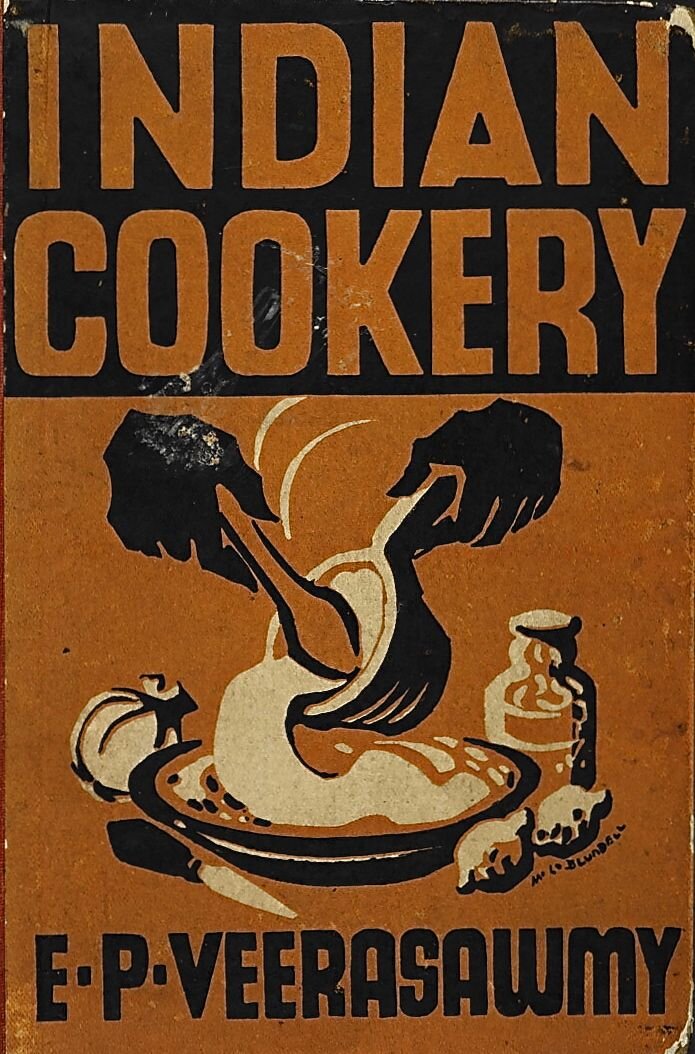

But scattered between rants on undependable servants, these books allude to the beginnings of a cuisine that started borrowing from its surroundings. While housewives blundered on attempting to recreate classic French cooking, with dishes like chicken quenelles and vol-au-vents, in their Indian kitchens, they also began to adapt to their new home, experimenting through recipes like Chili Toast or Eggs a la Byculla. They also perpetrated some modern-day appropriation, naming recipes such as Kasoundé, originally a Bengali recipe for mustard chutney called kasundi, repackaged to be more accessible to the very British housewives.

Colonialism also introduced vegetables that previously didn’t exist in India — non-native ones like cabbage and cauliflower — and made others like onion and garlic, previously only used in Mughlai cuisines, more prevalent. It also created what is considered a fundamental component of Indian cuisine: curry and curry powder. Curry powder, an invention of the British, began as a generic blend of spices that form the base of another generic dish called curry, which was later assimilated and transformed by Indians themselves.

Authenticity is an odd concept. It only comes into existence when you are confronted with something you believe to be inauthentic. Something that challenges what was taken for granted in mainstream culture. It may never have actually existed, but it can represent an idealised time, place, or dish, that materialises when the status quo is challenged.

Once the British began co-opting spices, Indian gourmands were forced to re-examine what they considered to be authentic Indian cuisine. Sitting alongside British household guides were a trickle of cookbooks written by upper middle-class Indian women, like Pragya Sundari Devi. Their very public entry into the publishing world reflects a parallel shift in Indian society at the time. Middle-class Indian men and women began to break away from their extended families to create nuclear units, and with that transition, cemented the identity of wife as housekeeper: one who was in charge of the nutrition and good health of her household.

Prajnasundari Devi | Image source Wikimedia Commons

Society began to frame the responsibilities and duties of the woman around cooking nutritious and tasty food for her husband, instead of relying on servants. This resulted in more culinary journals and cookbooks proliferating. To be clear, this was strictly a privileged Indian, upper-middle class trend, targeting the literate. But in these cookbooks, generic British curry powder was dismissed and instead, the term came to represent unique spice blends that formed a flavour base for each dish.

These cookbooks also demonstrated a mind-bending cross-pollination of ingredients, recipes, and names for these recipes. Dishes that used native, pre-colonial vegetables like wax gourd (patol) were called ‘firingi (foreign) curry’. Quietly, recipes began to include onion and garlic (new non-native vegetables) into dishes like lamb curry or egg curry. And finally to complete the circle of borrowed references, these guides introduced reimagined recipes for British dishes, under the guise of recipes for mutton chop or potato stew, using indigenous ingredients like ghee (clarified butter), an essential component in Hindu religious festivals.

The invention of such recipes could be viewed from an aspirational lens, where upper/middle-class Indians wanted to be considered civilised or acceptable to their oppressors, whom they worked for in government jobs: a sisyphean task ultimately, since the British never changed their view of the ‘natives’. Nevertheless, this gave rise to a fusion or hybrid cuisine, where the oppressed themselves began to borrow and morph appropriated ideas from the oppressors with no sense of the irony in the process.

Naming a thing matters. When something is called Kasoundé, or flaky bread, or a ‘demure cousin of lychee’, you define the boundaries of what it is. Or more importantly, what it is not. A flat-bread is not a roti or a chapati or naan. It brings to mind something closer to the bread that accompanies your wine and cheese. The name you choose washes away the strangeness and the difference of the thing, making it more acceptable and amenable to the consumer.

So, what is authenticity? These days, I cannot imagine an Indian dish without onions. And modern Indian cooks like Madhur Jaffrey use generic curry powders in their recipes all the time. If you go far back enough, everything comes from somewhere else. Everything is borrowed and authenticity is only called into question when there is an invader (real or perceived). When Bon Appétit changes recipes, it isn’t because their recipes are any less authentic than firingi-curry. It is because they haven’t done the work, the hard graft of learning about the hands they steal from. There is no context, no byline; only theft. And that is modern-day colonialism. It is slow and insidious; a burrowing. Without realising it, without constant vigilance, you change with it. If you don’t call it out, name it, face it, you become the coloniser of your culture. People talk of colonialism vs indigenousness. Appropriated or authentic. But the truth lies in a much greyer region.

Banner image credit: The Greasy Spoon

Nisha Sudarsanam is a writer exploring the intersection of food, women, colonialism, and art.

ALSO ON THE GOYA JOURNAL

Neo-nomad cuisine of Central Asia | Terrence Manne