Don't trash that! Pits, Peels & Pig Brain

Priyadarshini Chatterjee traces the economic crises, resource shortages and culinary ingenuity that spawned some of the most delicious dishes across cultures, where trash ingredients are the star.

Talk about 'posto', the deliciously earthy and nutty poppy seeds that liven up a Bengali meal, and the archetypal khadyoroshik Bengali is likely to get sentimental. And while posto is also used in other cuisines, none use it with as much gusto, or as prolifically, as the Bengalis.

But, Bengal’s passionate love for posto traces its origin to more harrowing times, under the British Raj. Having recently discovered the lucrative, illegal opium markets in China, the British soon transformed lush agricultural land in Bengal into money-spinning opium poppy fields, with little regard for the region's economy.

What followed was a rising number of farmers crippled by opium addiction and shortage of food produce. However, In the meantime, as food historian Chitrita Banerji points out, "...the Bengali culinary imagination found extensive application for the enormous quantities of poppy seeds, called posto in Bengali, that had suddenly become available." In the face of hardship, resourceful housewives desperate to put together a meal for their families, saw a delicious, and economic (no longer!) opportunity in the giant heaps of dried poppy seed left as trash outside the opium factories.

In a region ravaged by famines, exploited by colonial greed, and plagued by the horrors of partition and its subsequent displacement, such culinary up-cycling was often stimulated by dire necessity, and perhaps, a hunger-induced understanding of the value of food. Lucky for us, it led to the discovery of some incredible flavours in the most unusual places. That explains to some extent, the impressive assortment of dishes drummed up with everything from peels and stalks of vegetables, to seeds and rogue leaves, to fish bones and innards.

Simple stir-fries made with bottle gourd and potato peel, unctuous fish-fat fritters, and mushy chhachra trumped up with assorted veggies like the Malabar spinach, pumpkin, aubergines and fish head (ideally of the Hilsa), to a range of baataa (pastes) put together with peel of pointed gourd or raw banana, to leaves of cauliflower, and even shrimp head, especially popular in East Bengali homes.

Some of these dishes were perhaps born in the frugal, strictly vegetarian kitchens of Bengali widows. Confined by oppressive culinary stipulations, they would often experiment with the little they had at their disposal, to add variety to their scanty meals. Besides, minimizing waste was a cherished kitchen ideology, crucial to domestic economy, and making optimal use of ingredients was the ultimate symbol of a woman’s culinary ingenuity.

Zero-waste cooking is, of course, not limited to Bengali kitchens. Rajasthan, for instance, has an interesting tradition of cooking with peels, seeds and pits that are often also the most nutritious parts of a vegetable, steeped in curative virtues. “Our grandmothers were far more involved with the food they cooked in the kitchen, and their culinary creativity often stemmed from a better understanding of ingredients,” says Udaipur-based Vidhi Jain, a learning activist and a vehement proponent of the virtues of slow living.

So, instead of tossing those mango peels, rich in fibre and antioxidants, thoughtlessly into the bin, they are dried in the sun, boiled and cooked with a host of pickling spices to make a delicious side dish. The stones, also dried in the sun, are cracked open to take out the kernels, known to cure diarrhea and reduce cholesterol, and used to make pickles. The nutrition-packed rind of the watermelon, or empty pods of green peas make for favourite seasonal curries.

“One of the most delicious dishes to come out of my grandmother’s kitchen was the karele ke chhilke ki sabzi,” Jain tells me. “She would chop the bitter gourd peels, into fine bits, toss in besan, salt, turmeric and red chilli powder, and cook in oil tempered with mustard and cumin seeds. A generous sprinkling of aam-choor sealed the deal,” she adds. The peel of ripe bananas, on the other hand, chopped into tiny bits, made for a quick and delicious stir-fry.

Cut to present day, and the country is plagued by acute food wastage. According to one study, 40 per cent of the food produced in India goes to waste. While another states that food wasted in India is equal to the total food consumed by the whole of United Kingdom. The statistics are staggering. From the time of harvest, to various stages of transportation and distribution, there’s wastage at every point.

But what should be of immediate concern to us is the nonchalant wastage of food in our homes. Besides, there’s often more nutrition and flavour lying discarded in our waste bins, than on our tables. A little bit of imagination could not only help us make our kitchens sustainable and economical, it is likely to unlock flavours we didn’t know existed! We merely need to peek into traditional kitchens across the country for a serious dose of inspiration.

In my maternal grandmother’s kitchen, few things were tossed into the trash. She would whip up sweet, fluffy fritters with ugly, blackened bananas, or crisp, savoury ones with bottle gourd leaves slathered with sharp mustard paste, a sweet and spicy khosha chachchari put together with a medley of vegetable peels, usually gleaned over a few days, or a fiery kanta chachchari made with reserved bones of the bekti, that would have been filleted for a paturi or fish fry the previous day.

Again, every time she made her famous potol’er dolma, she made sure that the seeds of the potol she would scoop out to make room for her minced fish stuffing didn’t go to waste either. She would stir-fry the seeds in mustard oil tempered with Nigella seeds and green chilies, with a sprinkling of salt and turmeric powder, and relish it with hot rice.

I had forgotten all about the Potol seeds until recently I discovered a similar recipe in Pragya Sundari Devi’s celebrated recipe book Amish o Niramish Ahar, published at the turn of the last century, where she also writes about the curious Potol Beechir Nona Malpua – savoury fritters made with a batter of flour, chickoo pulp and seeds of ripe pointed gourd, flavoured with minced ginger and green chilies, and fried in pure ghee. Besides, there are recipes for mustard laced snake gourd skin, wrapped in banana leaves and roasted, and fritters dressed with the fibrous core of sweet, red pumpkin.

Seeds of pumpkin, on the other hand, are the prime ingredient in Kumro Beechir Paan Pitha, a now-rare sweetmeat made with khoya, coconut, semolina and a paste of pumpkin seeds. The recipe has been archived in Bipradas Mukherjee 1904 cookbook Mistanna Pak. The book also lists a recipe for a camphor-scented payesh made with jaggery and a smooth paste of jackfruit seeds.

Jackfruit seeds are also used extensively in kitchens across the south. Known as Chakkakuru in Kerala, the seeds are stir-fried with coconut, chillies and other spices to make a thoran, or added to tangy and spicy curries cooked with raw mango or drumsticks, or with small prawns.

Blogger Shireen Sequeira tells me that a traditional curry made with Taikulo (a herb that grows wild in the Konkan region during the rainy season), hog plums and jackfruit seeds, that is a monsoon favourite in Mangalore. Jackfruit seeds are also cooked with Mangalore Cucumber or Southekayi, a kind of field marrow, in coconut-based gravy.

No part of the Southekayi goes to waste either. In Udupi kitchens its seeds are used to make spicy rasam flavoured with fenugreek and coriander, while piquant chutney is made out of its yellow peel. The peels of the pomegranate, on the other hand, are used to make a traditional tambuli perked up with cumin and pepper.

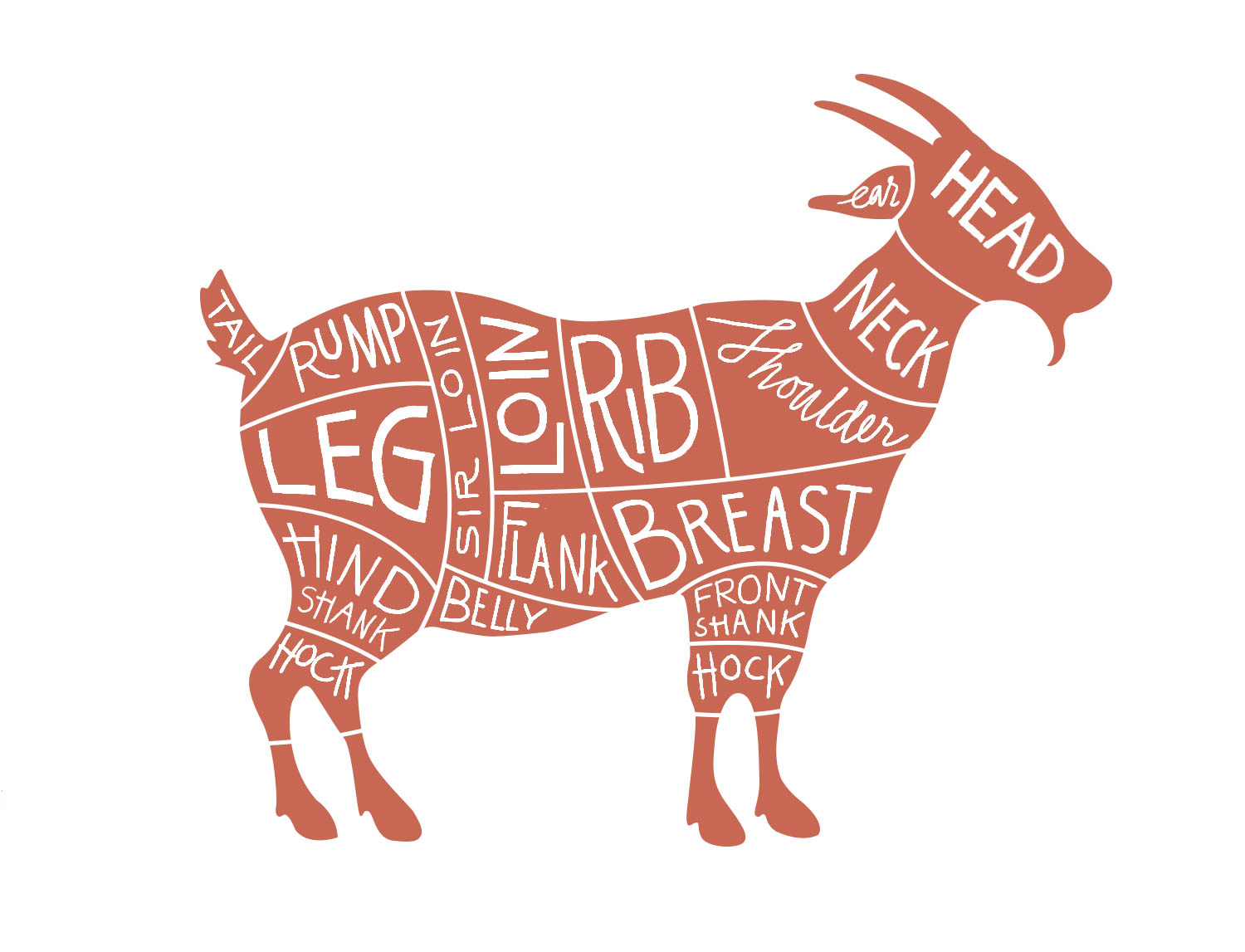

Over in a meat-laden Naga kitchen, discover the delectable virtues of lesser cuts of meat and for a few lessons on nose-to-tail cooking. The Nagas, in general, waste little. Their largely non-discriminatory eating culture stems perhaps from a past steeped in political upheaval, rural poverty and a serious scarcity of resources. Again, their tribal lifestyle meant that they were dependent on foraging and hunting for food. Hunted animals would usually be shared among large numbers of people, sometimes the entire village. Nothing was to be wasted.

Passionate pork lovers, the Naga kitchen wastes no part of the prized pig. “We eat everything including kidney, intestines and blood,” my friend Elika Awomi, tells me. The pig’s gall bladder, stuffed with king chilies and other spices, is boiled and slowly smoked over an open fire (ubiquitous in Naga homes), another much-loved speciality. “The head of the pig is not only a coveted delicacy, it is also a sign of respect towards the guest it is served to,” says Elika. The brain is ground into a paste and used to thicken the curry.

The pig’s brain is also crucial to the Doh Khleh, a perennial favourite among the Khasis and Jaintias of Meghalaya. First boiled, wrapped in a banana leaf, and then chopped up, the brain is added to a mix of boiled pork meat, ideally from the pig’s head, finely chopped onions and ginger. The dish is a classic accompaniment to what is perhaps the best-known Khasi dish, the Jadoh, a rice-based dish loaded with meat. Interestingly, the original recipe for the Jadoh requires the rice be cooked in pig (or chicken) blood before being mixed with the meat. Or would you fancy pig offal, intestines et al stewed in pork blood?

Basically, there is a whole world of untapped flavours, nutrition and other gastronomic virtues right inside your kitchen bin, and it is time to dig in. All you need is a dash of imagination and the determination to fight wastage. Yes, you can take inspiration from the Rene Redzepis and April Bloomfields of the culinary stage, or you could simply turn to your grandmother to learn a thing or two.

Priyadarshini Chatterjee is an independent journalist based out of Calcutta. Her work has appeared in publications like India Today, The Telegraph, Live Mint and The Hindu Businessline.

Illustrations by Rashmi Tyagi. Find more of her work here.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE