Fuel for the Fire: Inside the Community Kitchen of Shaheen Bagh

Shalom Gauri writes about the community kitchen that feeds the 24x7 anti-CAA protests that have been held at Shaheen Bagh, through one of the coldest winters that Delhi has seen in over 100 years. The protest is now in its 30th day.

On December 19, 2019, I stood outside Town Hall in Bangalore, packed in among hundreds of other people protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). As Indian flags were waved, and posters of Ambedkar and Gandhi held up to the sky, a glint of plastic caught my eye. At first we didn’t know what they were; little packets rained down over our heads and into the crowd. Should we run, should we hide, what new trick did the police have up their sleeve this time? But no, a man standing next to me laughed as he caught a packet in his fist, they’re packets of water! Tracking down the source, I found two men standing by an auto rickshaw full of stacked cardboard boxes, unloading and distributing several packets of free drinking water for the protestors. Soon, bunches of bananas followed, and packets of biscuit!

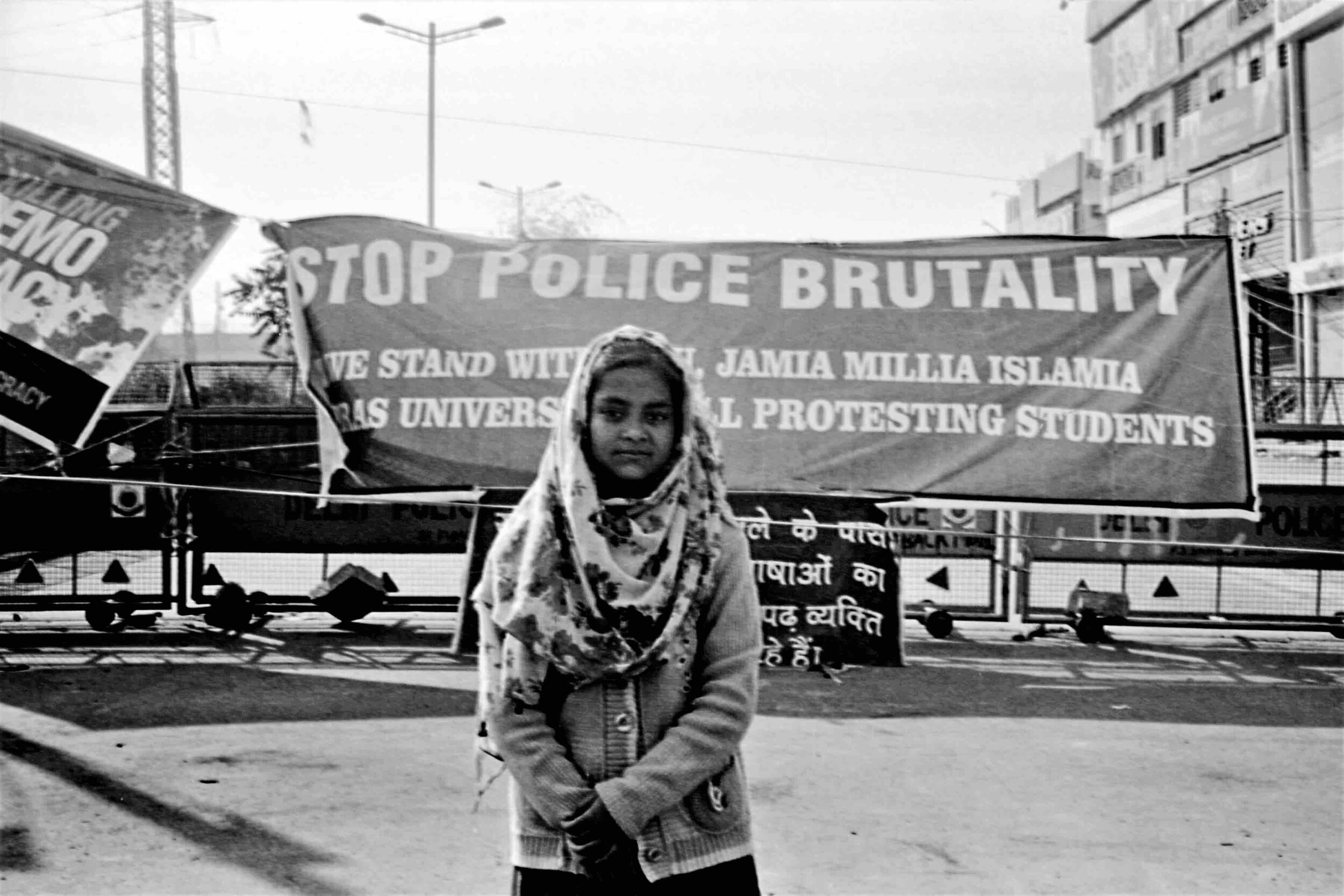

Where were these supplies coming from? Who were the people collecting and distributing them, and where were they getting the money? On June 13th last year, Inkstone had published an article titled “How do Hong Kong protestors eat, rest and pee?” As anti-government protests increase in number, scale and duration across the world, these practical questions become some of the most pertinent ones for organisers to tackle. In Lebanon, bakeries work all night to supply free Man’oushe for protestors; in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square the story is much the same. In Sudan, Awadeya Mahmoud’s free chai and food was a source of much inspiration and strength for the people; in Hong Kong Sogno Gelato owner, Mr. Chung, is known among youngsters for his free ice cream and distribution of protest gear that comes along with every meal. Here in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh too, food is central to the growing community of men and women who have been protesting against the CAA and the National Register of Citizenship (NRC) ever since last month’s police violence against students at Jamia Milia Islamia University.

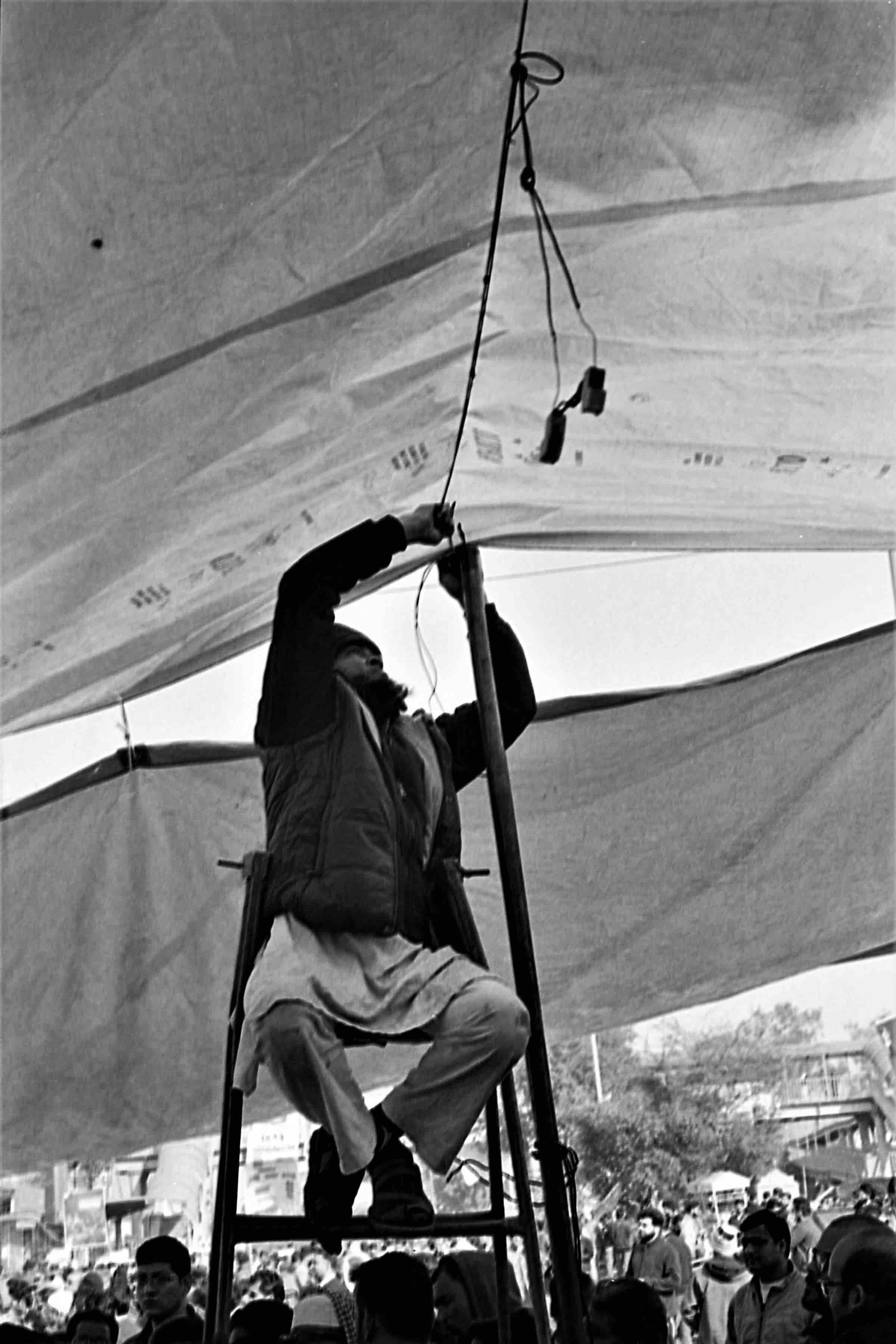

“If there’s anything we need help with, there are more than 50 people ready to help out,” explains Shalini, a student of Indraprastha College for Women. “People bring thousands of eggs and other food supplies,” she adds, noting that they’ve never once run out of food. “Nothing is cooked here. It all comes in trucks, packed from outside. We store it here until it’s time to distribute,” says Ahmed, a tailor by profession who helps manage the medical camp behind the stage. He takes us to a set of stairs sheltered by a large orange tarpaulin tied to the first floor railing of a shopping complex and we learn that all the large stores along the highway have been closed since the protests began on December 16th. Sitting in the balcony before the shopfront above are a group of children gathered around a guitar, their tiny but adamant shouts of “Azadi!” bouncing off the long drawn shutters.

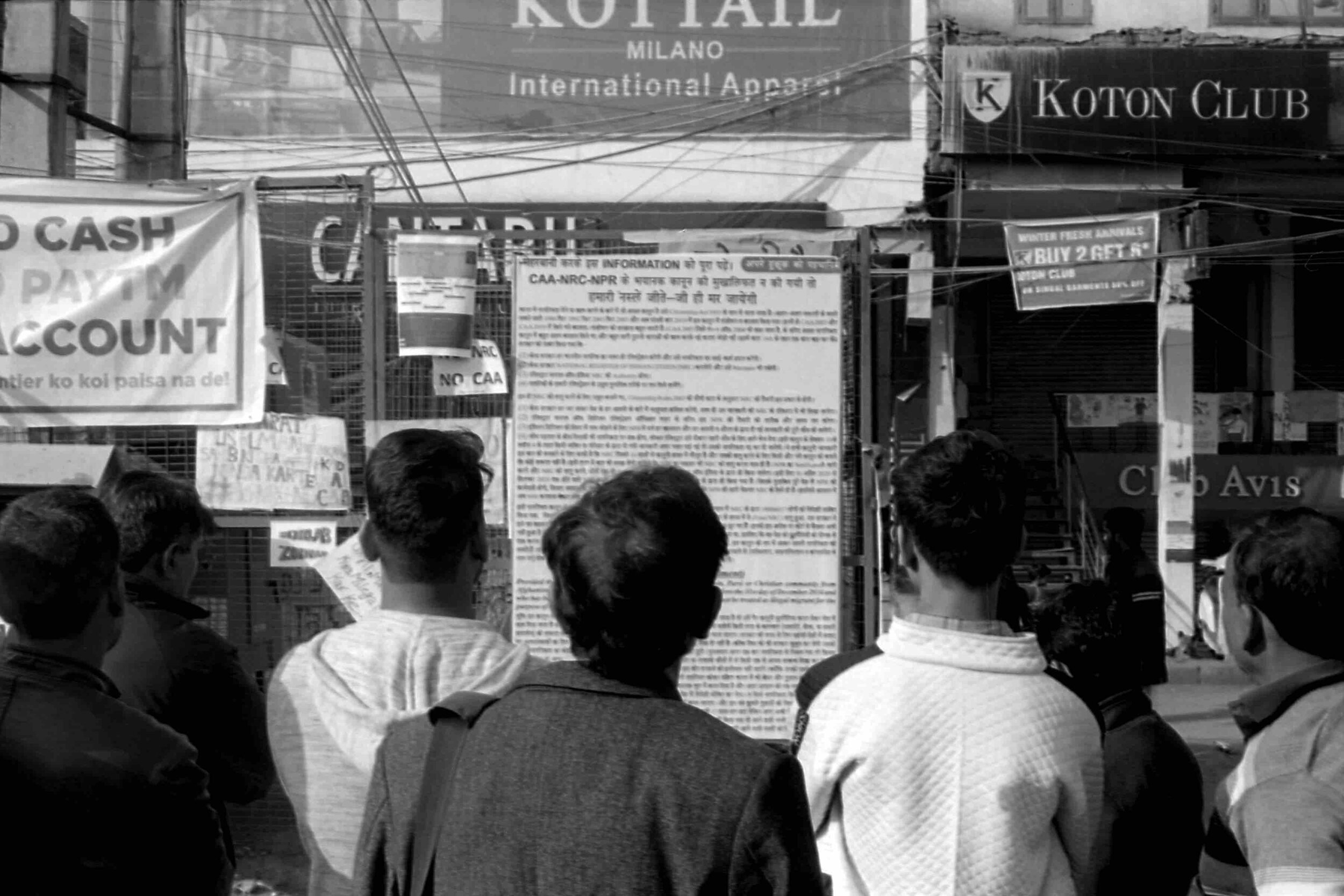

It is around 2pm when a small white Santro pulls up along the barricades. Three men get out and soon enough, five others from the neighbourhood gather to help. The backseat is stacked with packets of biryani. “We bring about 30 kgs of chicken and 30 kgs of rice,” says social worker Mustaqeem Ahmed. They also bring fruits such as chikku, anjeer and khajoor for those protestors who are performing roza, or fasting. The biryani is prepared near Chandni Chowk, in an area they refer to as Lal Kuan. Mustaqeem’s son is a student of political science at Jamia, he says when he learns that we are students too. They thrust more packets of biryani into our hands and insist that we eat with them. “It is not only Muslims that the RSS (the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) is targeting,” says one of his friends who moved to Delhi from Aligarh years ago. “It’s Dalits too.” We learn later that some of them are part of a Saifi Association and I am reminded of Muhahmed Akhlaq who was Saifi muslim too. A photograph of Babasaheb Ambedkar hangs inside the tent of the medical camp and the students’ tent by the large blue foot overbridge is filled with posters demanding the release of Chandrashekar Azad.

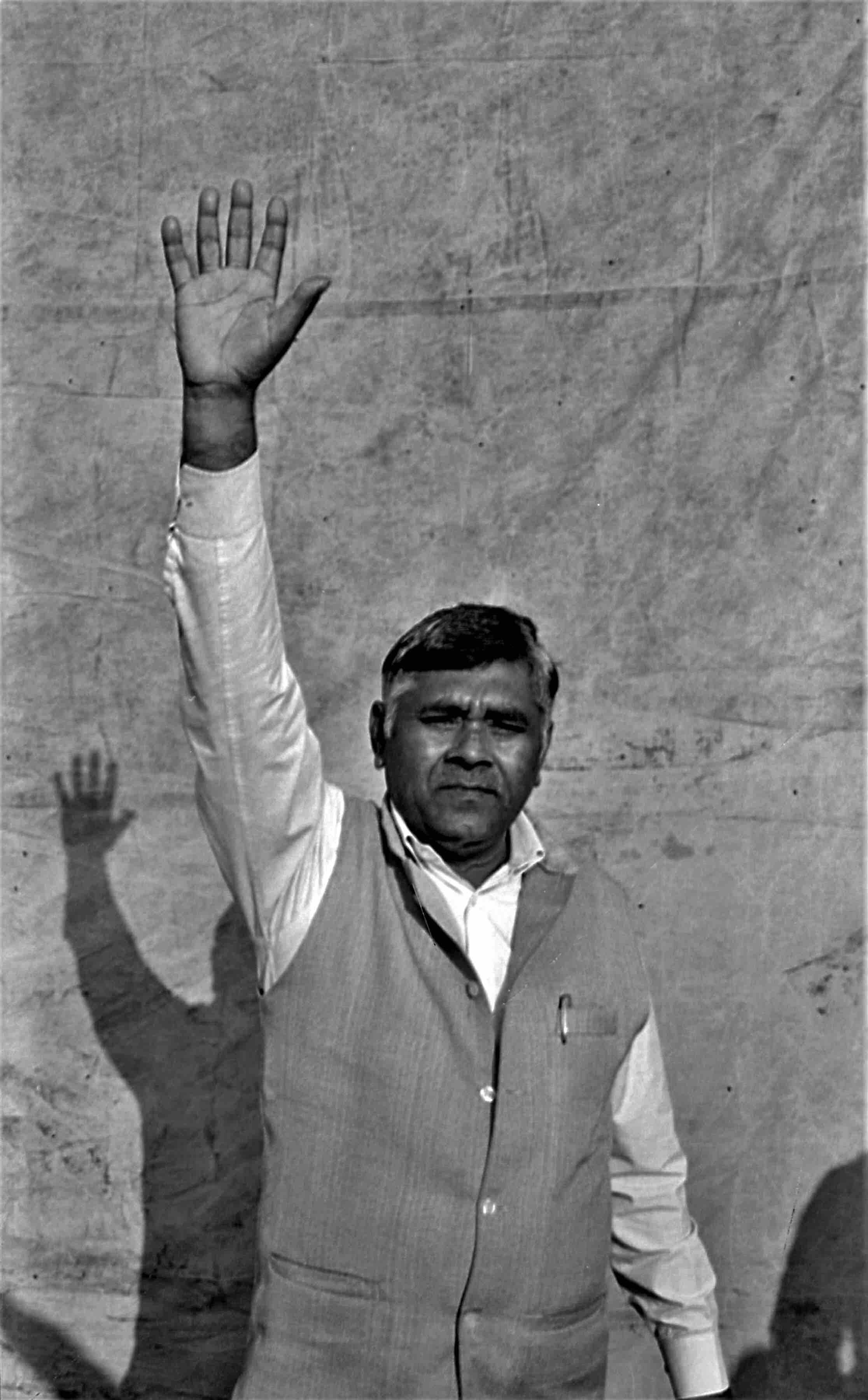

Photo by Shubhojeet Dey

Photo by Shubhojeet Dey

When asked about funds, Mustaqeem waves a dismissive hand. “No one gathers funds collectively,” he says. “Whatever we have in our pockets at the moment, we give. Be it a 100 rupee note or a 500. We trust the volunteers here to put it to use.” Nizar, a doctor at the 4-10 PM medical camp says something similar about medicines: “People come and ask us what we need and we hand over a list. it’s as simple as that,” he shrugs, adding that they’ve never run short of medication.

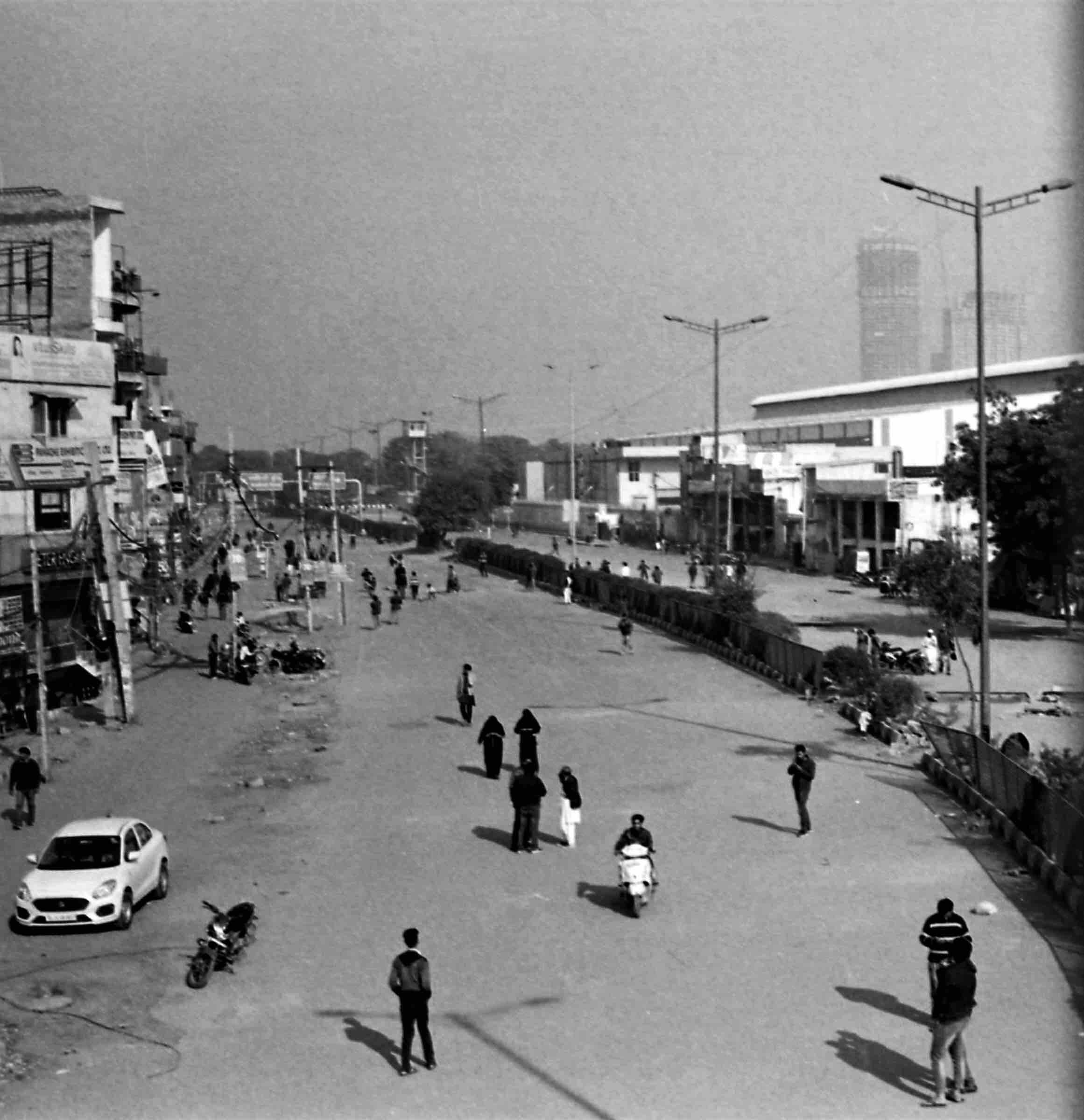

As news spreads of big multinational corporations running out of food supplies in protest-hit areas, it’s interesting to note that local businesses never seem to face the same problems. Their fight on the other hand, is not with the market but with the police. Telling us about initial attempts to cook food in large quantities on the spot, Ahmed describes the story of his friend and neighbour who, in the early days of protest, decided to collect money and make biryani on the highway. “He gathered enough money for more than 10 days!” he exclaims, shaking his head, explaining that the police didn’t like it at all; they argued that langars couldn’t be part of protests. Ever since, the idea of a community kitchen has been abandoned, replaced instead by a less formal system of donations, and food prepared from outside the area.

In Hong Kong too, there was news of the police arresting a chef at Kwong Wing Caterers for making free Christmas dinners for protestors. Similarly, state forces have targeted the Extinction Rebel Kitchen in London, dismantling kitchen tents one after another.

A global environmental movement, Extinction Rebellion, has made it a point to include kitchens at their protests for more reasons than one. To begin with, it solves the problem of protestors being called hypocrites for eating at chain restaurants, explains George Coiley, adding that all the food being vegan makes the act of eating itself a political statement. Given the somewhat reversed politics of food in India, at Shaheen Bagh the aim is to allow for a wider range of catering rather than a narrowing down of cuisines. “Hindu, Muslim, Veg yah Non-Veg, hum toh sab kuch lethe hain or dethe bhi!” says Mariyam Khan, taking a break from distributing food to rows of women seated outside the tent. From biryani and pulao to samosas, fruits and frooti, the women volunteers have a long list of items that they’ve received. “We used to get korma too, but we’ve asked people to stop donating that since it’s easier to serve single dish meals” explains Nazia Shakeel.

When asked where the food donations come from, Rizwana (fondly referred to as “Super aunty” by the kids running and playing in the area) laughs and says “Dekho, jo bhi sun raha hai, wo de raha hai,” and then rattles off a long list of places; Jaffarabad, Noida, Vasant Kunj, Vasant Vihar, Seelampur, Gurgeon, Ghaziabad. “We’ve even got donations from Dehradun, Patna, Bombay and Rajasthan!” exclaims another volunteer, Nazia Khan. All from the same neighbourhood, there is no leader among these volunteers and no single collection point, either. Whoever receives food brings it to the tent and it’s added to the pile until time for distribution. What helps perhaps is that most of these women have known each other for years, having lived and raised families in the same neighbourhood with most of their children even attending the same schools.

At various points along the divider, we see plastic dustbins overflowing with packets. Water too is distributed in sealed plastic cups and cardboard boxes are piled on the side by the dozen. “Please, apna kooda sab khud saaf karenge! Hum tumhare naukar nahi hai!” shouts Mariyam as she marches up and down between the rows of women. Initially no one cleared up the garbage, she explains, but then we saw videos of students from Jamia cleaning the road after the protests, and that put us to shame. Now, the entire area is regularly swept, and every afternoon the foam rolls inside the tent are put out in the sun and dusted. Squads of children with the Indian flag painted proudly across their cheeks patrol the area, ensuring that people remove their chappals before entering.

Just as we turn to leave, Mariyam stops us and adds “if you’re writing about us, write this: tell them we don’t want any politicians’ help. Not from AAP, not from Congress. We’re doing just fine on our own.” Adding that people often have preconceptions about Muslim women being stuck to their homes and hijabs, she says, “Now we’ve shown them that we too can be out on the streets”.

As evening begins to fall, the crowd increases visibly and soon there are rounds of chai being offered on trays. We follow one of the tray-bearers Yasin Ali, a man from Assam who has lived in Delhi since 2006, and he takes us to two men standing by three large cans of chai. They’ve got about 12-13 litres in there, all prepared beforehand in their welding shop back in Tughlakabad extension. One of the men is from Jaipur and the other from Kalkaji. “We’ve been coming for the past three days,” they say. “Yesterday we brought biryani, today chai, tomorrow pulao.” Across the road from them is another group of men, gathered by the transformer adorned with massive posters with factual information on the CAA, boiling chai in a large vessel. This too, is distributed freely all night long to keep the women inside going, sitting as they are in the cold, newborn babies and all.

“In the past I refrained from attending protests, there was a lot of fear attached to it. Fear of being alone, of no help, sitting there with my mouth shut,” tweets Anisha Rego, a student from Bangalore. “I’ve come to realise that there’s no ‘correct’ way to participate though, I can’t scream but I can feed,” she says, describing her attempt to make brownies for the students who observed an all-night protest there last week. Antara, a PhD student at Jamia and full-time volunteer at the medical camp says something similar about her work: “For me personally, it’s better than just attending protests, because here there are immediate results; you actually feel like you’re of some use.”

From the boys taking shifts at the barricades to check IDs and prevent the entry of those looking to create trouble, to the girls clearing the roads to make way for ambulances, there is a role for everyone to play at Shaheen Bagh. Centred around the fiery women who have stayed strong for 30 freezing winter days now, these anti-government protests remind us of those who keep it going, fuelling the fire from the periphery with hot food, hot chai and some much needed inspiration.

Shalom Gauri is a student of History and Journalism currently based out of Delhi. Occasionally, she is brave enough to blog the things she writes.

ALSO ON THE GOYA JOURNAL

Neo-nomad cuisine of Central Asia | Terrence Manne