How to Treat the Natives and Other Lessons from the Colonial Kitchen

Aparna Balachandran writes about a 19th century colonial cookbook, Culinary Jottings for Madras, an instructional for the English housewife that is peppered with recipes and a generous smattering of racism.

Brigadier General Arthur Robert Kenny-Herbert is one of the more interesting late 19th century Anglo Indian cookbook authors. Writing under the nom de plume 'Wyvern', his oeuvre includes books with formidably long titles such as Culinary Jottings for Madras: A Treatise In Thirty Chapters for Reformed Cookery For Anglo Indian Exiles Based Upon Modern English and Continental Principles With Twenty Five Dinners Worked Out In Detail and Sweet Dishes: A Little Treatise on Confectionery and Entremets Sucrés (the entire corpus of his writings is now available here for the reader’s delectation).

Perhaps unusually for a man in the 19th century, and an army officer, the Brigadier was deeply interested in the culinary arts. So much so, that when he returned to England in 1894 after his long stint in India, he started the Common-Sense Cookery Association in Sloane Street, London. While posted in Madras he wrote regular columns in the The Madras Mail, Madras Atheneum and The Daily News that contained recipes, and anecdotes about the joys, travails and frustrations of running an English kitchen in India. In 1878, these were compiled and published as Culinary Jottings from Madras. Extremely successful, and running into several editions, it is written in a humorous and anecdotal manner and is dedicated to the 'Ladies of Madras.' The ladies in question were the well-off, but not overly affluent, English housewives in the city who were advised on how to produce European meals in an Indian context, and how to deal with native domestic help. In Culinary Jottings, Kenny-Herbert has the unmistakable tone of a man who considers himself an expert with a sense of humour. Whether English housewives who actually dealt with the time-consuming and difficult task of running of their households in an unfamiliar country found the Brigadier patronising rather than entertaining, is something we have no way of knowing.

Culinary Jottings covers an impressive range of topics, from the management of the cook, choosing the ideal kitchen equipment, and stocking the larder, to cooking methods and recipes for every kind of meal whether a party or 'camp cooking' The book ends with thirty menus — for parties of different sizes, as well as home dinners with detailed instructions on the preparation of each course, from appetiser to dessert. A major concern of the Brigadier was which native ingredients could be adapted or used as substitutes in his recipes. The scraped root of the drumstick or moringa tree was seen as an excellent substitute for horse-radish, for instance. Not so mint, which often used in place of parsley, was denounced as the 'bane of the cook-room' and 'absolutely penal!' Unless absolutely essential, tinned foods were frowned upon (Interestingly, however, in 1893, the Brigadier provided the annotations for John Moir’s Catalogue of Tinned Foods). Madras was replete with fresh meat and fish, and 'English' vegetables were procurable from the cooler climes of Bangalore and the Nilgiri hills.

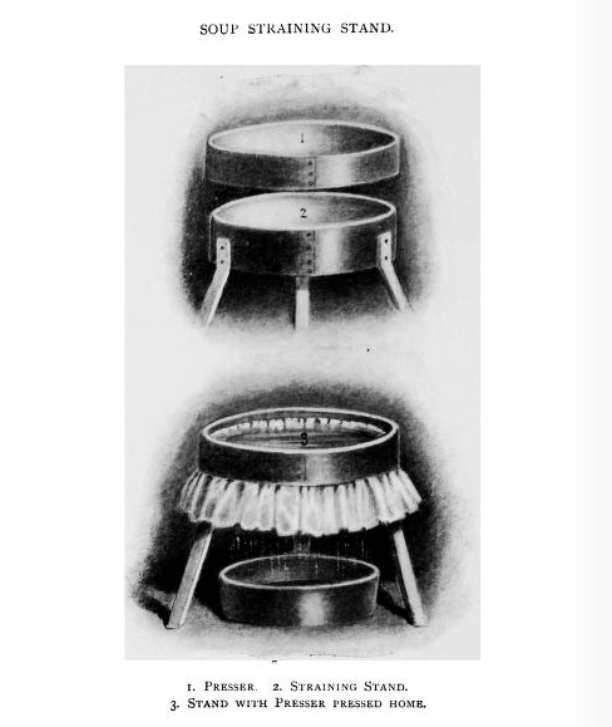

Illustration of a soup strainer from Common-sense Cookery for English Households

Kenny Herbert’s work has often been regarded as part of that corpus of 19th century Anglo Indian cookbooks that showcased the cuisine born out of the interaction between English housewives and their Indian cooks — examples include mulligatawny soup, kedgeree, pish-pash, and above all, curry. However, while respectful about the past, the Brigadier was quite clear that as far as he was concerned, the days of the East India Company, when Englishmen ate curries at home and at social occasions, albeit washed down with copious alcohol, had passed. Writing in 1878, he pointed out that 'Our dinners today would indeed astonish our Anglo Indian forefathers. With a taste for light wines, and a far more moderate indulgence in stimulating drinks, has been germinated a desire for delicate and artistic cookery. Quality has superseded quantity, and the molten curries and florid compositions of the olden times — so fearfully and wonderfully made — have been gradually banished from our dinner tables.' Speaking of mulligatawny soup, much touted as the encounter between an English soup and the South Indian rasam, he argues that it was so highly flavoured and filled with condiments and spices, that any English diner would find 'the delicate power of his palate vitiated.' Kenny-Herbert makes it abundantly clear that his is an informed choice, and not one borne of a lack of knowledge about the foods he was rejecting as suitable for the English in India. In two rather grudging chapters he claimed that native cooks no longer made decent curry and provided his own recipe for curry powder, in the absence of which the reader is asked to buy the only good shop brand, Barrie’s 'Madras'.

Culinary Jotting’s marginalisation of curry reflects a shift in the nature of British colonialism in India that historians have often referred to — the hybridity of the social and cultural world of early colonialism had given way to a deepening and racialised distance between the British and their Indian subjects by the latter half of the 19th century. Indeed, the Brigadier was emphatic that his book was assuredly not meant for the Anglo-Indian in England who yearned for curry with misplaced nostalgia, but for Englishmen in India who ate 'English and continental food'.

In rejecting the early colonial engagement with Indian food, Kenny Herbert did not advocate going back to an authentic English cuisine. Instead, as was the fad in late Victorian England, Kenny Herbert was fascinated by French food, and was an enthusiastic proponent of 'copying the culinary triumphs of the lively Gauls'. He drew his inspiration from the French chef and pâtissier, Jules Gouffe and above all from the epicure and gastronome, Brillat Savarin, whose legendary tome, The Physiology of Taste: Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy 'ruminates on the art and philosophy of food and eating'. He also considered himself a very modern cook, with a deep interest in matters of nutrition, and Culinary Jottings is peppered with quotes from the writings of English medical experts like Edwin Lankester and Henry Thompson. The Brigadier was also a strong advocate of the 'reformed' kitchen in India that was clean, ventilated and fully provided with the new cooking equipment available in the market such as Warren's Cooking Pot and Duff’s cooking ranges. If the natural propensity of the native cook for filth had to be countered, it was up to his English employers to provide him a sanitary cooking space.

Warren's Cooking Pot

Image credit: chestofbooks.com

Unless one is reading Culinary Jottings for its recipes, the most interesting aspect of the book is its discussion of domestic help in the late 19th century European household — above all the native cook in Madras — that Kenny- Herbert generically calls 'Ramasamy', the equivalent. he claims, of 'Martha' in England. He advises the English housewife to not leave the task of dealing with the cook to the butler, encouraging her to 'make a friend of your chef, you cannot weary of the petty larceny, carelessness, ignorance, stupidity, and an apparently wayward desire to thwart your desires to the utmost.' Like the Indian munshi or scribe, who would not admit that he did not understand a passage in English, the butler could not be trusted to pass on information to the cook, and it was better to speak directly to the cook in the same 'Madras pigeon English' that he used. Infinite patience, explained the Brigadier, was necessary to deal with native servants. Lacing his racism with sexism, he remarks tongue in cheek, that this advice was unnecessary for women: 'Ladies I know, are never angry, and even when a little put out, do they not contrive to hide their feelings with a sweet subtlety which men can envy, yet never hope to acquire?'

Kenny-Herbert does not mention Ramasamy’s caste in his observations, but in all probability, he came from a low or outcaste community. As European households began to populate the slowly growing port city of Madras from the 18th century onwards, domestic servants including sweepers, cleaners, cooks, butlers and wet nurses, were hired to work at these establishments. Coming from the lowest rungs of the social ladder, and often having escaped a harsh existence as agricultural labourers, these men and women had positions in the most intimate spaces of the European home, something that would have been impossible in an upper caste Hindu family. Kenny Herbert’s account gives us a fleeting glimpse into the social dynamics of the relationships created, albeit completely framed by the static figures of the frustrated Englishman dealing with the unintelligent but stubborn native cook.

It does not require a great deal of reading to argue that Kenny Herbert’s thoughts on Ramasamy were distilled from his attitudes towards Indians in general. Ramasamy was childlike and dimwitted, and unless properly trained would 'cling affectionately to the ancient barbarisms of his forefathers.' His lack of hygiene had to be kept firmly in check by providing him a 'reformed' kitchen space, and the accoutrements of cleaning cloths and washing soda. Weighing scales and a clock in the kitchen were essential to deal with his propensity to guess at weights and times instead of paying meticulous attention to recipes. For Kenny-Herbert, the ability to cook intuitively was something that was reserved for Europeans. Humorous anecdotes illustrate how the hapless Englishmen was thwarted in his desire to introduce elements of a modern kitchen into his Indian home. One story recounts the Brigadier visiting a friend in the hills, where he noticed that the outer vessel of a Warren’s cooking pot was being used to carry water for the bath. On enquiry, his host sadly declared that the inner vessel had been made into a 'capital tom-tom for beating a sholah.'

Kenny-Herbert is very clear that his observations about methods of cooking, and the procurement of ingredients was only applicable to Madras; he confesses annoyance at writings that made general statements about the 'Indian lifestyle' that had no relevance to the city. For instance, the abundance of fresh fish and vegetables in Madras made the reliance on tinned food — a hallmark of European cuisine in India — irrelevant. What stands out in Culinary Jottings however, is that its deep, and even affectionate, knowledge of the climate, produce and European society of Madras, never breached its imperial limits to cultivate any kind of interest in the history, culture or culinary traditions of its native inhabitants.

Aparna Balachandran teaches at the Department of History, University of Delhi. Her work looks at the city of Madras (now Chennai) under early East India Company rule.

Banner image: British Raj by MF Husain

ALSO ON THE GOYA JOURNAL